The Monastery of Dečani

History, art and manuscript heritage

Danica Popović, Žarko Vujošević (Institute for Balkan Studies – Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts)

History

The monastery of Dečani (fig. 1) was built in the first half of the 14th century when both the Serbian state and the reigning holy dynasty of Nemanjićs flourished. It was an era abounding in military victories, territorial and economic expansions, extraordinary thought and spiritual ascents, and brilliant literary and art achievements. From that point of view, the endowment of King Stefan Uroš III (1322–1331), who was named Dečanski (of Dečani) after it, was a true representative of its time. In line with the Nemanjić dynastic tradition of ktetorship, established in the 12th century with the monastery of Studenica, the monastery of Dečani not only displayed all characteristics of the tradition – organisation of monastic life, cult of the holy dynasty founder, architecture and wall painting – but surpassed them in format, richness and monumentality. It contained the best, most precious and most beautiful the Nemanjićs could offer the Saviour for the salvation of their souls and eternal remembrance, but also to add to the glory of their dynasty and “fatherland”.

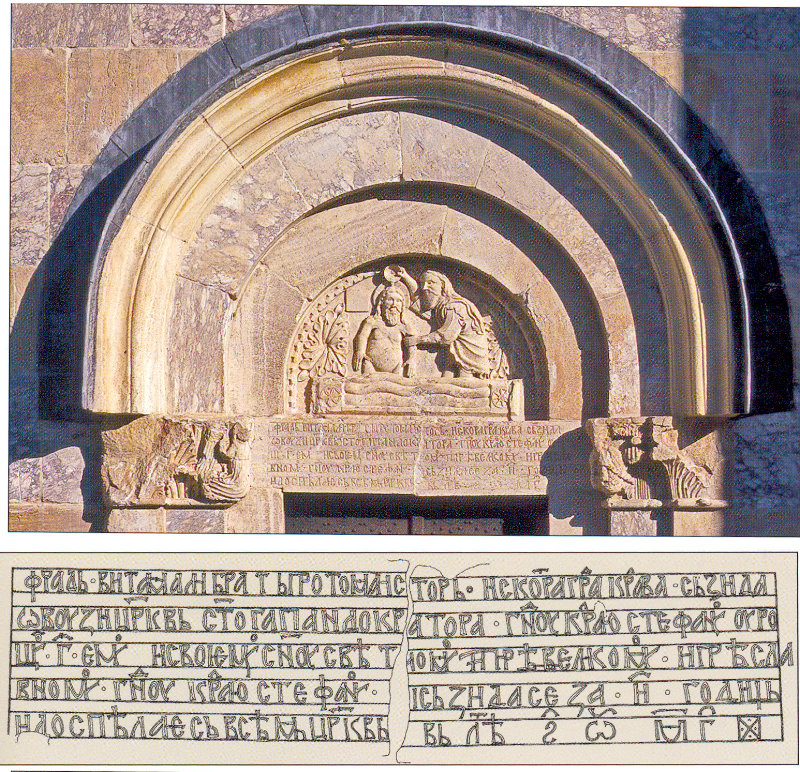

A preserved inscription referring to the monastery's construction (fig. 2) places its beginning in 1327, and its completion in 1334/1335. Eschatologically influenced and imbued with the idea of dynastic continuity, King Stefan of Dečani's motives for this ktetoric endeavour were, in a picturesque manner, revealed in hagiographic and diplomatic sources. From the very beginning, it was decided that the monastery, including a church dedicated to the Pantocrator (fig. 3), should be an coenobium and the burial-place of Kings. By his first Foundation Chrysobull in 1330 the King provided funds for construction of the monastery as well as a huge land property. In addition to the main ktetor, the construction of the monastery was taken care of by the King's son, King and subsequently Emperor Dušan (1331-1355), as well as by the archbishop Danilo II and Arsenije, the monastery's first hegumen. There are also records of an unusual ktetoric contribution to royal memorials by a lord of Pećpal family from Hum. The glorious days of Dečani lasted hardly more than half a century, since the monastery was destroyed by Turks immediately after the battle of Kosovo (1389).

In the second half of the 14th and the first half of the 15th century, at the time of Turkish conquests and destructions, the monastery was taken care of by successors of the dynasty of Nemanjićs, rulers coming from the families of Lazarević and Branković. Thanks to them, the monastery of Dečani preserved both a good deal of its properties and its status as a spiritual and cultural centre. In 1455 the monastery eventually fell into Turkish power that lasted till the 20th century. It lost a good deal of its landed estate, but managed to preserve some important privileges that were substantiated by the Sultan's firmans. After the Patriarchate of Peć was restored in 1557, the monastery enjoyed a flourishing period, as evidenced by the works of art and liturgical objects. But the record of misfortunes that befell the monastery of Dečani during its long and dramatic history by far prevail. During and after the Austrian-Turkish wars in the late 17th and in the 18th centuries the acts of violence, that were present since the 15th, and especially since the second part of the 16th century, sharply increased in number. The same was true also for the 19th century when the monastery brotherhood was exposed to a systematic Albanian terror, as well as to Roman Catholic unionits' pressures.

The end of the First World War in 1918 brought final liberation to the monastery and its gradual recovering began under the sponsorship of the Karadjordjević dynasty. The monastery of Dečani survived the Second World War thanks to the Italian carabinieris' protection, but the post-war period was marked by the rule of communists who deprived the monastery of large land properties. However, major works were performed on protection and conservation of the monastery's antiquities. The time we live in meant new and difficult challenges for the monastery. After witnessing armed clashes and bombings in 1999, as well as the establishment of KFOR military presence in Kosovo and Metohija, the monastery has existed in isolation, protected by Italian troops (fig. 4). The fact that, despite its turbulent past, the monastery has survived in a perfect state of preservation has many times been described as a miracle that the Dečani monks attribute to the Holy King’s celestial patronage.

Since the 14th century to our times St. Stefan of Dečani's relics have been the sacral core and spiritual base of the monastic community of Dečani. The emergence and development of Stefan's cult was a very complex process, which included several distinct phases. The phase one began with miraculous revelation of the King's sainthood (ca 1340), when his relics were transferred into a valuable shrine (fig. 5), and a posthumous portrait, depicting him as a saint who intercedes for his posterity, was painted above it (fig. 6).  Thanks to the texts of Grigorije Camblak, who was once hegumen of the monastery of Dečani, the second phase (ca 1400) established the Holy King's basic identity of a ruler-martyr, thus defining the future course of celebration of saints. In the third phase, that coincides with the restoration of the Patriarchate of Peć in second half of the sixteenth century, the cult was spreading, as shown by synaxaria, but also by the King's increasingly frequent portrayal in devotional paintings.

Thanks to the texts of Grigorije Camblak, who was once hegumen of the monastery of Dečani, the second phase (ca 1400) established the Holy King's basic identity of a ruler-martyr, thus defining the future course of celebration of saints. In the third phase, that coincides with the restoration of the Patriarchate of Peć in second half of the sixteenth century, the cult was spreading, as shown by synaxaria, but also by the King's increasingly frequent portrayal in devotional paintings.

The narrative icon of painter Longin from 1577 is certainly a masterpiece among them, both from ideological and artistic point of view (fig. 7). In spite of all misfortunes the cult of St. Stefan of Dečani continued to persist within his monastery, and the belief in miraculous healing capacity of the King's relics was traditionally maintained not only among Serbian orthodox, but also among Albanian population. Even in the latest warring events the Holy King's sacral aura did not lose its appeal. Every Thursday the moleban (Parakleisis) to the Holy King is served in the Monastery, a deeply moving event: apart from the monks and the remaining members of the Serbian community, the relics are paid devotions by members of international forces of different religious denominations and nationalities.

The location of monastery of Dečani is also unique. The Monastery is situated at the foothill of the Prokletije Mountain, beside the river Bistrica, at the very edge of the Metohija Valley which in its South-West part turns into a gorge. A traditional belief that it was St. Sava of Serbia himself who picked the location for a church to be built, and a brilliant literary depiction of its natural beauties in the works of Grigorije Camblak point to its holy character. The author described in detail all parts of the monastery: huge fence walls with the entry tower, and within the walls there are cells and a spacious refectory, as well as a kitchen and a bakery. Such a spatial and architectural design, which corresponded to the idea of a higher order defining coenobitic monasticism, has been preserved in monastery of Dečani to the present time. It is a male coenobitic monastery with about thirty monks and novices. The head of the brotherhood is Teodosije, the Vicar Bishop of Lipljan. In addition to its liturgical life and spiritual function, the monastery is a living entity performing a number of activities, from agriculture and artistic creation to the Internet website presentation, and has a crucial influence on the Serbs living in Kosovo and Metohija. Only remnants of other forms of monastic life, such as sketes and hermitages, which once were widely practiced in the gorge of the river Bistrica, exist today.

Art

A church, constructed by builders from Kotor under the guidance of the master builder Fra Vita, is situated in the middle of the monastery complex. It is by all aspects a masterpiece of medieval architecture: by its size and monumentality, by spatial architectural structure of the church as a five-aisle domed basilica, and by an exquisite multicoloured marble facades. The impression of splendour is further intensified by a sculpture depicting a marvellous mixture of biblical scenes, real and fantastic animals, plants and ornaments. Although belonging in style to the late romantic period, the sculpture is in full harmony with the spiritual ambience of an orthodox church. It conveys messages of the similar kind: all created beings, in their multiplicity and diversity, are reflections of the world where virtue and sin are in conflict, and their ultimate purpose is to praise the glory of God. The interior of the church is no less solemn and was highly admired for its height by the contemporary people (fig. 8). Authentic pieces of medieval furniture and equipment have been preserved to the present time: the iconostasis and marble parapets between the aisles, bronze horos, the marble throne, royal tombs, hagiasma. Therefore, the statement of the monastery's ktetor made in the Foundation Charter that he adorned the Home of the Lord Pantocrator with “all internal and external beauties”, and also the belief of many generations to come that the beauty of the church in Dečani surpasses all ideas, are easy to accept.

But the most impressive part of the church interior are its paintings. Their magnitude is truly reflected in the fact that during ten years of frescoing in the church (that ended in 1347/1348) about one thousand scenes and individual saintly figures were painted. They were arranged in about twenty hagiographical and liturgical cycles and even more subject groups. The entire Christian salvation history, including all its important phases – from Christ Pantocrator (fig. 9), the story of Genesis and original sin and the revelation of Christ's redemptory work through his incarnation, miracles, teaching and the Passion, to foundation, consolidation and expansion of the Church of the New Testament, and, finally, to the Second Coming and the ultimate salvation of human race – is in an extraordinary systematic manner displayed in the Monastery of Dečani. In other words, the Monastery of Dečani offers a unique concept of church paintings representing an image of Kingdom of God and reflecting it as fully as the liturgy. Within such a general order, Serbs are depicted as members of the community of the elect. Upon entering the church a believer is faced with a number of historical figures – in the first place with the ktetors, Stefan of Dečani and his son, the King and later the Emperor Stefan Dušan, as well as with their holy ancestors. The church also accommodates Serbian church superiors and deserving Dečani hegumens. Thus the basic message communicated to the faithful was the one about the Nemanjić dinasty’s sainted forebears and God-chosenness.

It is not surprising that over centuries a royal endowment of such a rank and wealth has compiled an extraordinary treasury. The merit for foundation of the treasury belongs to the ktetors of the church, as mentioned in the Foundation Charter, but its subsequent enrichment was due to numerous contributions by kings, church prelates, but also by multitude of believers and pilgrims who came to pay respect to the Holy King. Within the Serbian boundaries, the wealth of the monastery of Dečani's treasury is second only to that of the monastery of Hilandar. A unique collection of icons, comprising ninety very old and artistically important ones, has been preserved in Dečani to the present time.

Equally important is the collection of objects made of precious materials, some of which were part of the original treasury. Due to the fact that during its six and a half centuries long history the monastery of Dečani has never been deserted, exposed to fire or left roofless, it has preserved the most important collection of wooden objects, deep-carved and decorated with intarsia, dating from the 14th to the 17th century.

The Manuscript Heritage

Books are a special and precious part of the Monastery of Dečani treasury. About 160 manuscripts and 17 old printed books, which were part of the former monastery library, have been preserved to the present time, making it a Serbian collection second only to the one in the monastery of Hilandar. The manuscripts are written on parchment and on paper and almost all of them are in medieval Serbian. Judging from their contents, they were mostly intended for liturgical use: Tetraevangelia, Apostola (Epistle Lectionaries), Hieratica, Menaia, Horologia. There are also works of patristic and ascetic literature, a few of the oldest Serbian verse Prologues, as well as manuscripts directly associated with the cult of the Holy King Stefan of Dečani. Of special importance is the collection of charters and other documents bearing witness to the long and exciting history of the monastery.

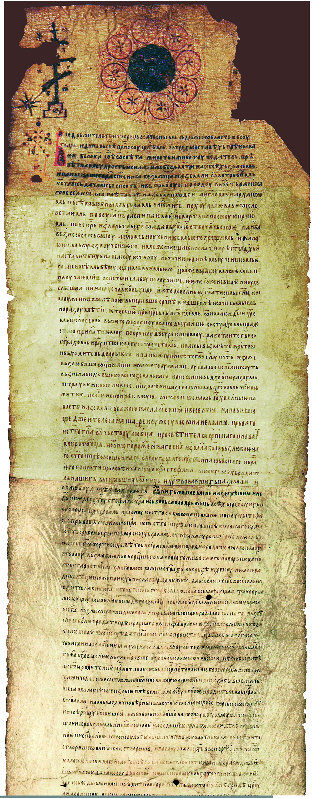

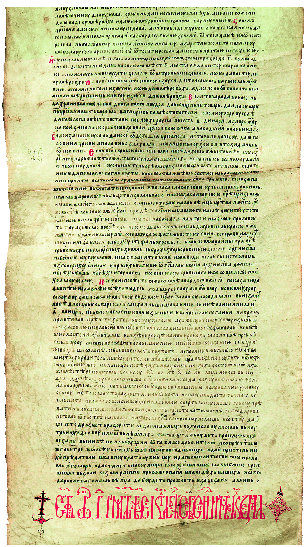

The Foundation Charter of the monastery (The Archives of Serbia) was issued by Stefan of Dečani in 1330 (fig. 10). It is a representative document in the form of a scroll, written on parchment with the ktetor's calligraphic signature at the bottom. The introductory part of the charter presents the King's pious and dynastic, eschatologically coloured, motives for erecting the monastery, as well as autobiographical information. This document, issued by Stefan of Dečani with the approval of the state council and the head of the church, allowed the foundation of the monastery to be laid and provided funds for its construction and for establishment of the brotherhood.  The charter also provided the monastery of Dečani with huge land properties in Kosovo, Metohija, Montenegro, and the Polimlje region. The shorter, ceremonial version of the document cites the names of villages, hamlets, and summer pastures that were received as a gift, as well as their boundaries, and a list of individuals with their rights and obligations. The Second Chrysobull of Dečani, which was lost, came into existence before deposition of Stefan of Dečani on August 21, 1331, since it bears his signature, as well as the signature of the king Dušan. It is a broader version of the Foundation Charter, written in the form of a book, and it contains the lists of people living in each village or in summer pastures. It also lists new donations, mentions the King's visits to the monastery and cites the measures regulating monastic life. The Third Chrysobull of Dečani (The Archives of Serbia) was issued in 1343–1345 and represents the ultimate version of the charter. It bears the signatures of Stefan Uroš III and of Stefan Dušan. The information about the original ktetor are missing since they were no longer of current importance, but the information on new properties were entered and all changes in landed estate were recorded. These charters were the most relevant cadastre-legal documents of the monastery and were subsequently used to document its rights. They were guarded as the most precious possessions, and in the centuries to come they were held in greatest esteem and carefully copied, fully and in part. They also served as a model for the Charter of the Princess Milica (nun Jevgenija) issued in 1397 (The archives of Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts; fig. 11). Having visited the monastery with her sons, she wanted to become its new ktetor and paid for reparation of the damage caused to the monastery estate by the Ottomans. She also donated properties and some valuable objects, such as a bronze horos and books.

The charter also provided the monastery of Dečani with huge land properties in Kosovo, Metohija, Montenegro, and the Polimlje region. The shorter, ceremonial version of the document cites the names of villages, hamlets, and summer pastures that were received as a gift, as well as their boundaries, and a list of individuals with their rights and obligations. The Second Chrysobull of Dečani, which was lost, came into existence before deposition of Stefan of Dečani on August 21, 1331, since it bears his signature, as well as the signature of the king Dušan. It is a broader version of the Foundation Charter, written in the form of a book, and it contains the lists of people living in each village or in summer pastures. It also lists new donations, mentions the King's visits to the monastery and cites the measures regulating monastic life. The Third Chrysobull of Dečani (The Archives of Serbia) was issued in 1343–1345 and represents the ultimate version of the charter. It bears the signatures of Stefan Uroš III and of Stefan Dušan. The information about the original ktetor are missing since they were no longer of current importance, but the information on new properties were entered and all changes in landed estate were recorded. These charters were the most relevant cadastre-legal documents of the monastery and were subsequently used to document its rights. They were guarded as the most precious possessions, and in the centuries to come they were held in greatest esteem and carefully copied, fully and in part. They also served as a model for the Charter of the Princess Milica (nun Jevgenija) issued in 1397 (The archives of Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts; fig. 11). Having visited the monastery with her sons, she wanted to become its new ktetor and paid for reparation of the damage caused to the monastery estate by the Ottomans. She also donated properties and some valuable objects, such as a bronze horos and books.

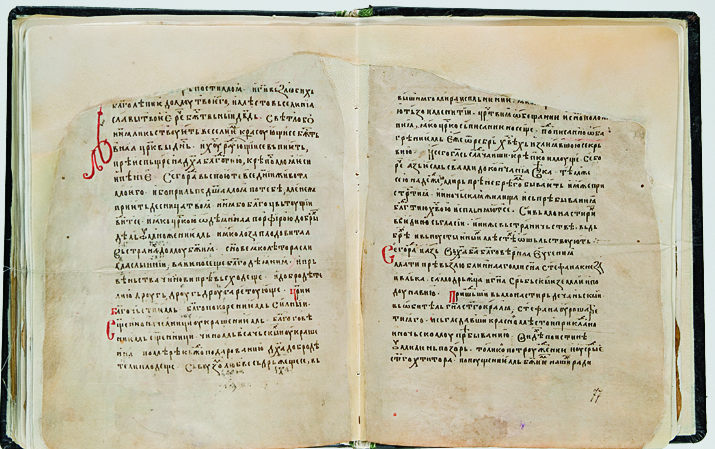

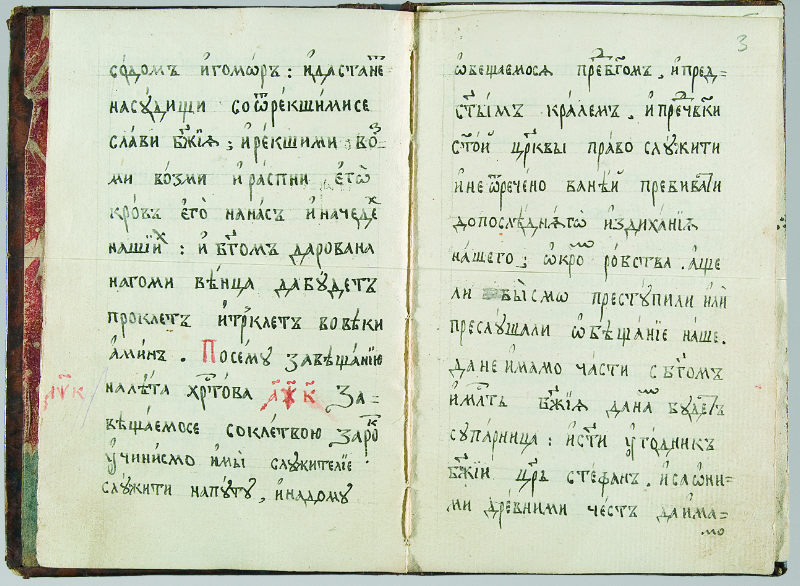

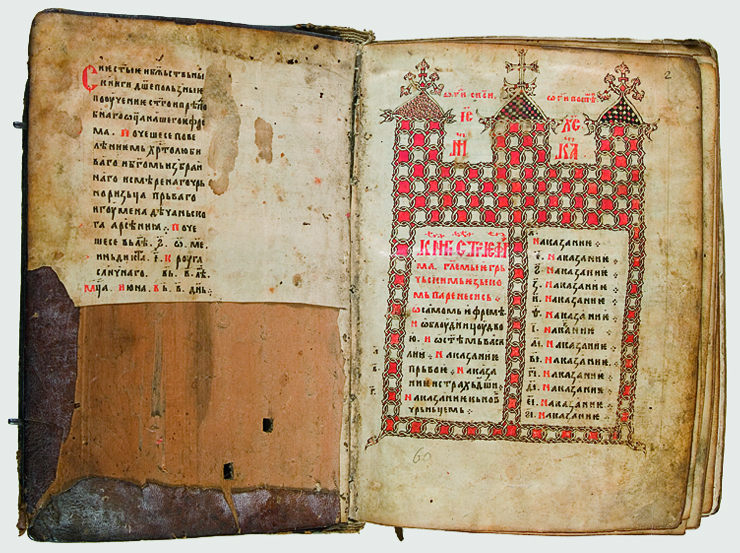

Among the written documents directly related to the monastery of Dečani several manuscripts attract special attention. Of greatest importance are commemoration books (paroussias). The oldest one that we know of, dating from 1572, disappeared when during the bombing of Belgrade in 1941 the National Library of Serbia was burnt down. Luckily, the Commemoration Book No. 109 from 1595 has been preserved (fig. 12). The order to make the book was made to the prominent copyist Dimitrije Daskal from Janjevo by prohegumen Viktor, at the time of hegumen Atanasije. Dimitrije made a very representative book, 43x29 cm in size, whose texts were written in black, red and golden letters, and the deacon Ananija created beautiful illustrations, the small flag at the cover page standing out among them. The book contains a great number of toponyms and the names of donators, as well as a number of notes written down within a period of three centuries, which make it a valuable document. The same goes for the Commemoration Book No. 149 dating from 1883 that was written by Lazar Nikolić, a teacher from Peć. The book contains unique notes from the time of horrible reprisals in the second half of the 19th century, after the Sultan declared jihad at the time of Greek–Turkish war, including the names of the monks who were killed.  But the ordeals that the monks of Dečani were subjected to are best witnessed by their Oath Book No. 152, which is unique in the whole Christian world (fig. 13). In 1720, at the extremely turbulent time after the Austrian–Turkish wars, the hegumen Melentije and twelve hieromonks took the oath not to leave the monastery. In time the number of monks who joined the oath increased and, in late 18th century, the Oath Book was made, citing the names of all monks who decided to express their devotion to the monastery in that manner.

But the ordeals that the monks of Dečani were subjected to are best witnessed by their Oath Book No. 152, which is unique in the whole Christian world (fig. 13). In 1720, at the extremely turbulent time after the Austrian–Turkish wars, the hegumen Melentije and twelve hieromonks took the oath not to leave the monastery. In time the number of monks who joined the oath increased and, in late 18th century, the Oath Book was made, citing the names of all monks who decided to express their devotion to the monastery in that manner.

Paroussia, dated to about 1818, which was written and illustrated by Aleksije Lazović, is of a special importance for studying history of the monastery. In addition to very nice illumination on historical themes, Paroussia includes a long text full of interesting and relevant information, and calling for donations when adopting monastic way of life. It also lists numerous construction and reconstruction works on the monastery ground recorded by haji-Danilo, the longstanding and deserving hegumen of the monastery of Dečani.

The way the collection of books of the monastery of Dečani came into existence and the phases of the process can today be reconstructed only in part. Most of the books contain no information on when and where they were made and such information are difficult to identify. However, thanks to filigranologic research, the dates of manuscripts that were written on paper, and even their origin, have been fairly accurately identified, while some of the copyists have been identified by palaeographic research. These researches allow us to perceive at least the general historical outlines of the Monastery of Dečani's library. The main stimulus had, no doubt, come from the ktetor himself, King Sefan of Dečani, who in the Foundation Charter of the Monastery, among the gifts received, primarily cites books. Unfortunately, the quantities and the contents of the books are not known to us.

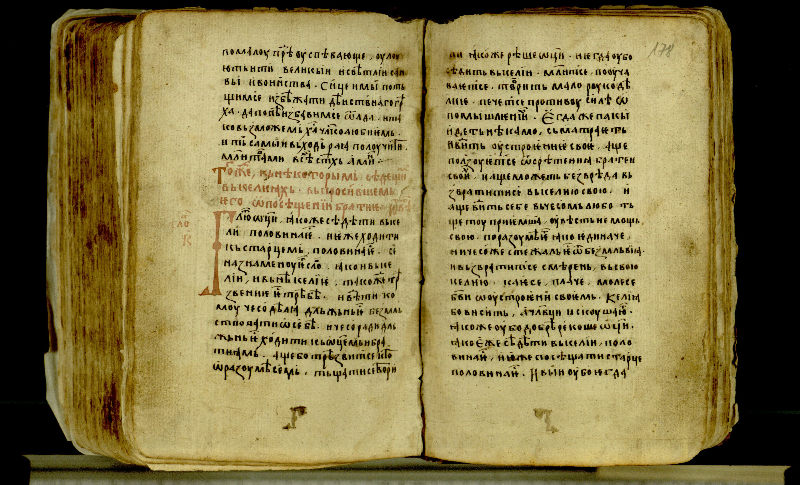

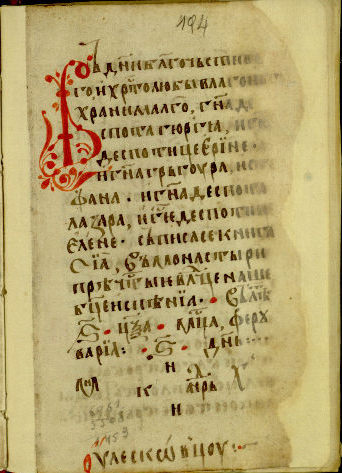

Most of the preserved books originate from the time of foundation of the monastery and from the early period of its existence. Today we know that the monastery came into possession of two important books thanks to its first hegumen, Arsenije. One of the books is Typikon (now in the Russian National Library in St. Peterburg, F.p.I, No. 93), which was written by the “sinful” Dobreta, who lived at the time of King Stefan Dušan (1331–1346), and the other is Parenesis of Ephraim of Syria (now in the archives of Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, No. 60) which is a richly ornamented manuscript written in 1337 by an unknown author (fig. 14). One of the oldest preserved manuscripts is the Story of Barlaam and Joasaph (No. 100) from 1330–1340, with supplements from the 15th and 16th centuries. The story, with a very wide ideological scope, ranging from asceticism to royal ideology, was written by not less than five scribes and their handwritings have been accurately identified. Menaion No. 94 originates from approximately same period (fig. 15). It is a large book of 467 sheets, written in small semiuncial letters, in dark-brown and cinnabar ink. Its scribes were three monks – Jefrem, Nikola, and Georgije – and it was written in the period 1340–1350. In the 16th century the book was supplemented by a fourth scribe. The manuscript contains a number of very interesting notes made by the scribes: they made a neat account of their writing shares, complained about poor quality of paper that regrettably resulted in their errors, hasted writing and blank pages. One of the copyists convincingly described his own poor health that made his life miserable and eventually caused his death, which was conveyed to us by the scribe who took over his job on the book.

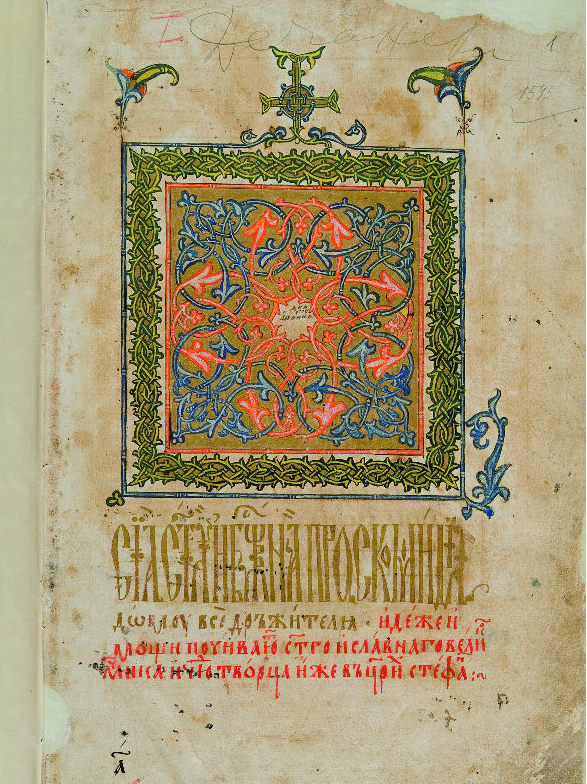

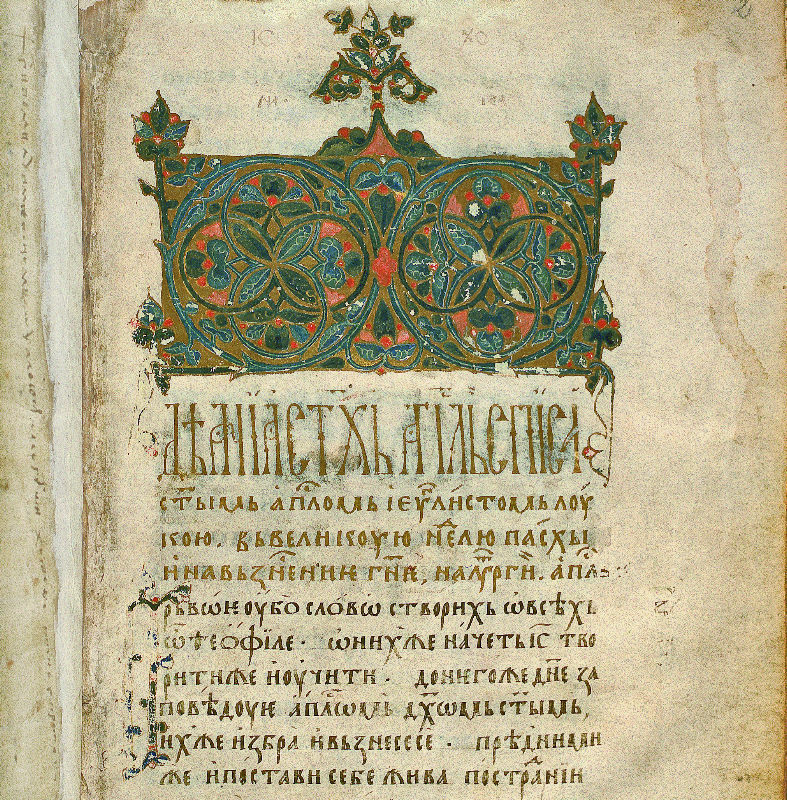

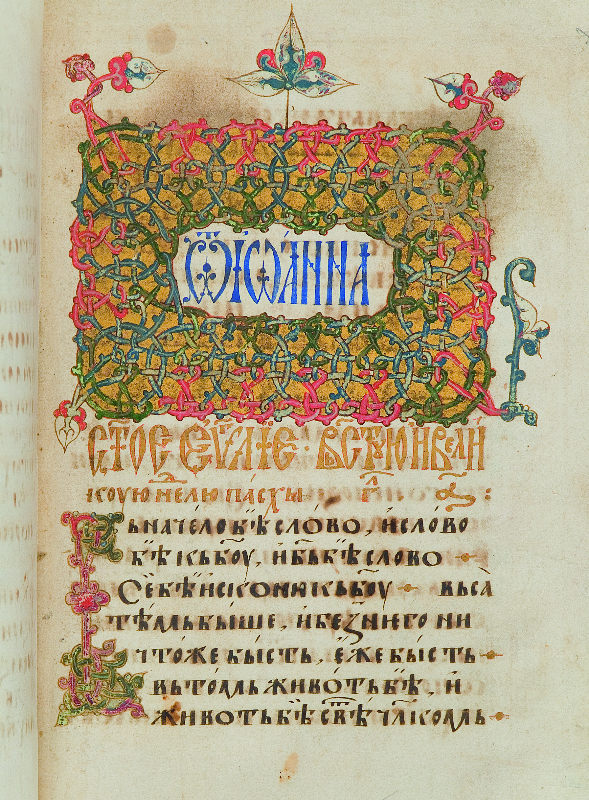

The assumption that the already cited monk Jefrem, i.e. the scribe who in 1351 copied Homilies of Gregory the Theologian (No. 92), could be the famous ascetic born in Bulgaria, and later on the Serbian patriarch Jefrem, who in the third quarter of the 14th century led an ascetic life in hermitages near Dečani and Peć, is tempting, but poorly substantiated. The oldest library of the monastery of Dečani also contained richly ornamented books, which is witnessed by Epistle Lectionary No. 25, originating from 1350–1360 (fig. 16). Its text was written in uncial letters, in black and red ink, using blue and golden colours, and it begins with a very nice small flag of Byzantine type in tempera and gold.

The assumption that the already cited monk Jefrem, i.e. the scribe who in 1351 copied Homilies of Gregory the Theologian (No. 92), could be the famous ascetic born in Bulgaria, and later on the Serbian patriarch Jefrem, who in the third quarter of the 14th century led an ascetic life in hermitages near Dečani and Peć, is tempting, but poorly substantiated. The oldest library of the monastery of Dečani also contained richly ornamented books, which is witnessed by Epistle Lectionary No. 25, originating from 1350–1360 (fig. 16). Its text was written in uncial letters, in black and red ink, using blue and golden colours, and it begins with a very nice small flag of Byzantine type in tempera and gold.

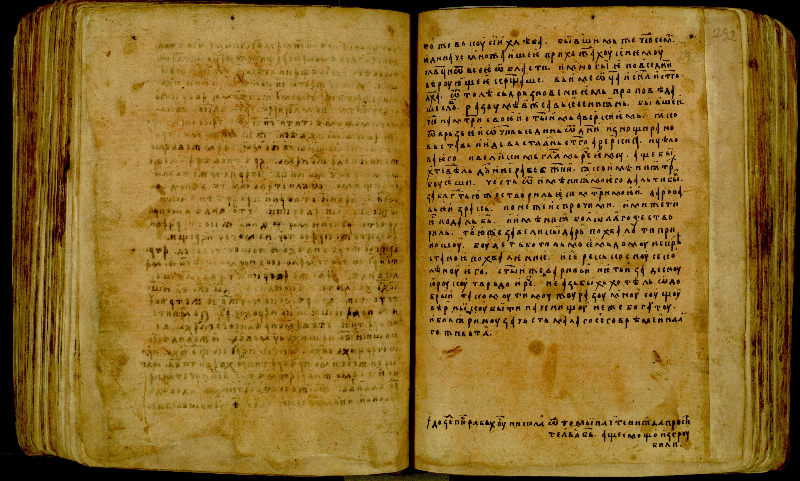

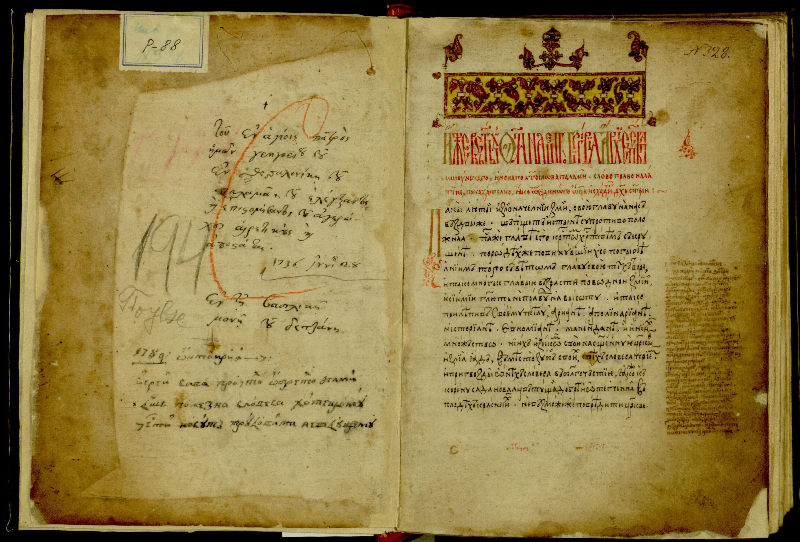

Although there are good reasons to assume that from the very beginning copying activities were practiced in the monastery itself, i.e. in its sketes, cells and estates, there are also facts showing that the brotherhood of Dečani very early turned to Hilandar for supply of books. Research of paper and watermarks led to the conclusion that as many as fourteen books from the period 1360–1370 were of the Hilandar origin, and it was also established that some of them were made by the most prominent Hilandar scribes. We shall mention only a few particularly interesting examples. “Heavenly Ladder” (No. 73) of John Climacus is one of the most influential books of Christian asceticism that was written by a Hilandar monk Josif Damjan about 1360. Pentekostarion (No. 62), called Lazarevac, originates approximately from the same period and displays very nice ornaments and calligraphic initials. The scribe Jov wrote down the following prayer at the end of the book: "My Lord Jesus Christ, I beseech thee with the prayer of Holy Mother who gave you birth and of all Saints to redeem the one who wrote these lines from eternal tortures – Jov the monk." The library of Monastery of Dečani had in its possession a copy of Tetraevangelion No.9 from about 1375–1380, the work of a famous scribe, “taha” monk Marko, the very same scribe who compiled the famous Collection of Lives of Serbian Saints and copied the Typikon of Hilandar (National Library of Serbia, No. 17), the only manuscript in the National Library of Serbia that “survived” German bombing in 1941. “Taha” Marko’s Tetraevangelion, of high artistic value, was written in uncial letters, in brown and red ink, and the flags and initials, illuminated in thick tempera and bright colours. The manuscript Homilies of Gregorios Palamas (No. 88), dating from 1360–70, has a prominent place in the Dečani collection (fig. 17). This anthology of statements and polemics of the famous Byzantine hesychast and his opponent Barlaam is important not only for being contemporary with the hesychastic conflict, but also for containing several texts that were not preserved in the Greek original source. Therefore, the manuscript is a must in studying of the Palamite movement which, as it is well known, had a decisive influence on the spiritual life of Byzantium in the second half of the 14th century.

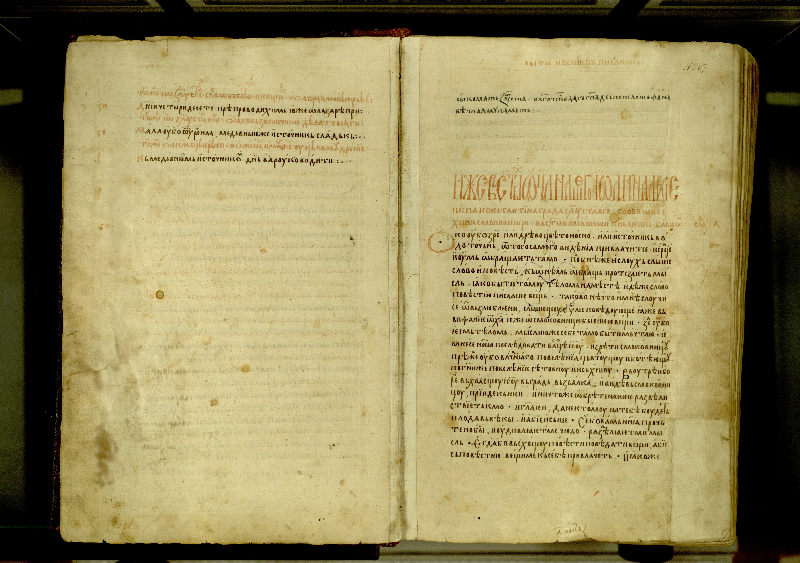

A special and very important group of manuscripts in the Monastery of Dečani originates from the last decade of the 14th century and is linked with ktetorship of the rulers of the Lazarević dynasty, beginning with the already mentioned visit of Princess Milica, later nun Jevgenija, to the monastery. It is an established fact that her son, Despot Stefan, was possessed a book from the Dečani collection, Homilies of St. John Chrysostom (No. 85), that was of an unusual size of 40,5x27 cm (fig. 18). That information, written down in exquisite letters at the beginning of the book, is not a note, but rather a specific ex libris. The ecclesiarch Barlaam had a crucial role in expansion of the library of the Monastery of Dečani in that period. He provided the monastery with the complete set of Synaxarion that had previously been included into divine service. In the book for March–April (No. 53) there is a note testifying that the book was written "during despot Stefan's rule, ... thanks to donation by ecclesiarch Barlaam". The scribe has been identified, by use of the attributive method, as Danilac Levooki (Left-eyed), a respectable copyist whose work is primarily linked with Hilandar, but also with the cells near the Patriarchate of Peć. He worked on two very popular ascetic literature books for the monastery of Dečani: Homilies of Abba Dorotheos (No. 79; fig. 19) and Patherikon (No. 96). The latter manuscript, containing short accounts of the life of monks, includes also a text mentioning Barlaam as donator, this time in the capacity of the Monastery's hegumen.

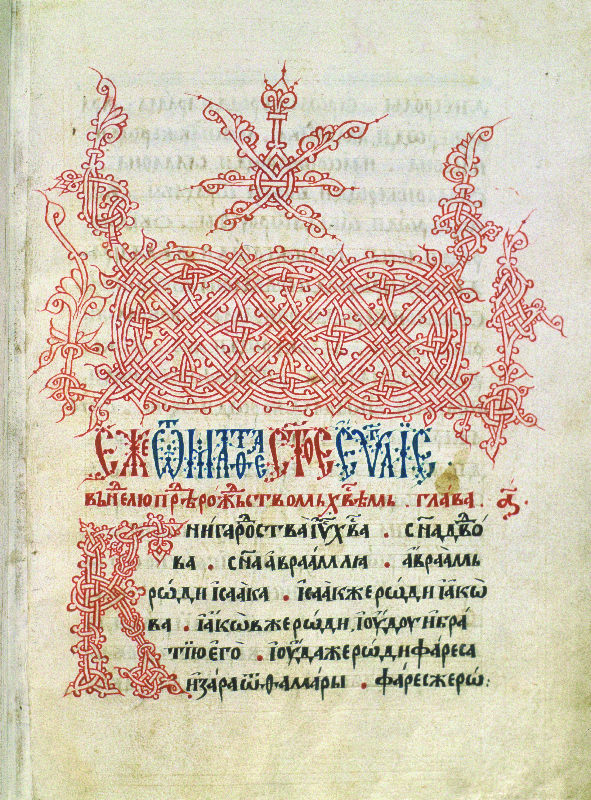

The flourishing period of bookmaking, which began at the time of the Lazarević dynasty, continued also during the rule of their successor despot Djuradj Branković (1427–1456), and his name has been immortalized in three books preserved in the Monastery of Dečani. Grigorije Camblak, while being in the office of the monastery's hegoumen around 1400, also engaged in writing. Both his Life and his Office served to lay the foundation for celebration of Stefan of Dečani. The oldest copies of the texts have been preserved in Collection No. 99 dating from 1430–1440, the work of hieromonk Grigorije, the leading copyist of his time. Of special interest is the contents of the Collection, which, in addition to Camblak's texts, includes Teodosije's Canons dedicated to Christ the Saviour, St. Simeon, and St. Sava, Lifes of St. Nicholas and St. George, as well as a selection of psalms. The same copyist worked in the period 1440–1450 on Lent Triodion (No. 64), nicely ornamented manuscript containing a text that is a valuable witness to the bookmaking activities at the Monastery of Dečani. The manuscript was made for the abba Arsenije who lived in the beautiful “desert” above the Monastery, with the Church of Three Holy Hierarchs was situated. It is, in fact, a skete of Dečani which has been recently identified and was traditionally known as “the Holy King's hermitage”. Researchers agree that in the first half of the 15th century the Monastery of Dečani was an important copying centre, which is indirectly, but convincingly demonstrated by considerably smaller number of manuscripts of Hilandar origin at the time. Nevertheless, books were procured from other sources, most probably from copying centres set up by despots Stefan and Djuradj. This is corroborated by ornaments in some of the manuscripts from Dečani, for example in Tetraevangelion No. 11 from 1430s (fig. 20), which allows close analogies with the kind of book ornaments used on the despot's domain.

Troublesome period following the Turkish conquests had been reflected in the monastery's book heritage as well. A striking example is the Euchologion No. 131 from 1453 (fig. 21). It was written by a monk called Nikandar, only four months before the fall of Constantinople. A unique note made by the copyist on the last four pages expresses a deep anxiety and abounds in eschatological thoughts. Expecting an imminent end of the World, Nikandar prays to Christ for mercy, to the Mother of God for mediation, and asks his brotherhood for forgiveness. Taking such circumstances into account, it is not surprising that in the Monastery of Dečani only a dozen of books from the second half of the 15th century have been preserved, and that they were mostly poorly ornamented and carelessly written.

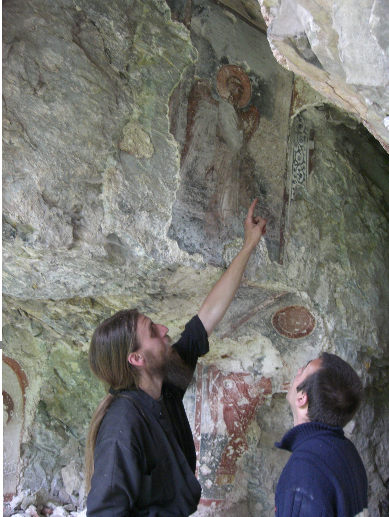

In time, the general situation went back to normal and the copying activities were revived. Their main centre was a skete in Belaja with a church dedicated to the Mother of God (fig. 22). The skete was the main centre of the kelliotes of Dečani.

There the scribe Nkandar wrote a number of books in late 15th and early 16th century, the information being available in Tetraevangelion No. 14 from 1494 (fig. 23).

That manuscript is a good example of Nikandar's work. He wrote his books in nice uncial letters, using large initials and exquisite small flags, composed of concentric overlapped and cleanly and accurately drawn circles, and, as a rule, without colours. Some of the books copied by Nikandar considerably helped to strengthen the cult of the Holy King of Dečani.

Divine services to Stefan of Dečani can be found in Synaxarion No. 59 for September–December, as well as in Psalter with Appendices No. 47. In about 1500, in cooperation with other scribes, Nikandar made Euchologion No. 134, which includes Parakleisis for St. Stefan of Dečani.

Divine services to Stefan of Dečani can be found in Synaxarion No. 59 for September–December, as well as in Psalter with Appendices No. 47. In about 1500, in cooperation with other scribes, Nikandar made Euchologion No. 134, which includes Parakleisis for St. Stefan of Dečani.

Although it is considered that copying activities in Belaja were discontinued already in 1520s, the preserved manuscripts bear witness to the fact that books kept coming to Dečani. Some of them were even luxuriously ornamented, such as Tetraevangelion No. 19) from 1550–1560, or the already cited Dečani Commemoration Book from 1595. About the same time, i.e. 1596–1598, the painter Longin, author of the famous narrative icon of the Holy King, wrote Akathistos of St. Stephen Archdeacon (No. 138). The fact that in that period many books were repaired and rebound clearly indicates the attitude of the monks of the monastery of Dečani towards books in the 16th century. Thus in the second half of the 16th century the copyist and bookbinder Jovan restored as many as twenty old books, and in mid of the same century hieromonk Mina "restored" manuscripts and documented his work by making notes.

Selected Bibliography

History, Art, Cult

- Батаковић, Д. Т. Дечанско питање. Београд 2007. [Summary: D. T. Bataković, The Dechani question]

- Григорије Цамблак. Служба светом краљу Стефану Дечанском, Србљак II, ed. Д. Богдановић, С. Петковић и Ђ. Трифуновић, Београд 1970, 305-349.

- Давидов, А., Г. Данчев, Н. Дончева-Панаиотова, П. Ковачева, Т. Генчева. Житие на Стефан Дечански от Григории Цамблак, София 1983.

- Данилови настављачи. Данилов ученик, Други настављач Даниловог зборника, Стара српска књижевност у 24 књиге. 7. Изд. Г. Мак Данијел, Београд 1989, 67-78.

- Дечани и византијска уметност средином XIV века, ed. В. Ј. Ђурић, Београд 1989. [Dečani et l'art byzantin au milieu du XIVe siècle, ed. V. J. Djurić]

- Ђорђевић, И. М. Представа Стефана Дечанског уз олтарску преграду у Дечанима, Саопштења 15, Београд, 1983, 35-43. [Résumé: I. Djordjević, La répresentation de Stefan Dečanski tout près de la cloison du sanctuaire à Dečani]

- Зидно сликарство манастира Дечана. Грађа и студије, ed. В. Ј. Ђурић, Београд 1995. [Mural Painting of Monastery of Dečani. Material and Studies, ed. V. J. Djuric]

- Ивановић, Р. Дечанско властелинство, Историјски часопис 4, Београд 1952-53, 173-226. [Summary: R. Ivanović, The Dečani Nobility]

- Манастир Високи Дечани. [Ed. by brotherhood of Dečani), Дечани 2007.

- Марјановић-Душанић, С. Свети краљ. Култ Стефана Дечанског, Београд 2007. [Summary: S. Marjanović-Dušanić, The holy king. The Cult of St. Stefan of Dečani, 565-583]

- Мирковић, Л. Живот краља Стефана Дечанског од Григорија Цамблака, Стара српска књижевност III, Нови Сад – Београд 1970.

- Мирковић, Л. Иконе манастира Дечана, Старине Косова и Метохије 2-3, Приштина 1963. [Résumé: L. Mirković, Icones du monastère Dečani]

- Нинковић, Л. Братство лавре Високих Дечана, Приштина 1988.

- Петковић, В. Р., Ђ. Бошковић. Манастир Дечани. I-II, Београд 1941. [Résumé: V. R. Petković, Architecture, Dečani I, 197-230; Zusammenfassung: Dj. Bošković, Die Malerei, Dečani II, 73-79]

- Поповић, Д. Под окриљем светости. Култ светих владара и реликвија у средњовековној Србији, Беоргад 2006, 143-183 [D. Popović, Under the auspices of sanctity. The cult of holy rulers and relics in medieval Serbia; Summary: The holy king Stefan of Dečani, 344-346]

- Поповић, Д. Српски владарски гроб у средњем веку, Београд 1992, 101-113. [Summary: D. Popović, The royal tomb in medieval Serbia, 189-201]

- Поповић, Ј. Житија светих за новембар, Београд 1977, 266-288.

- Соловјев, А. Кад је Дечански проглашен за свеца?, Богословље 4, Београд 1929, 284-298.

- Суботић, Г. Прилог хронологији дечанског зидног сликарства, Зборник радова Византолошког института 20, Београд 1981, 111-138. [Résumé: G. Subotić, Contribution à la chronologie de la peinture murale de Dečani]

- Теодоровић-Шакота, М. Прилог познавању иконописца Лонгина, Саопштења 1, Београд 1956, 156-166. [Résumé: M. Teodorović-Šakota, Contribution a l'etude sur le peintre d'icones Longin]

- Тодић Б., М. Чанак-Медић. Манастир Дечани, Београд 2005.

- Шакота, М. Дечанска ризница, Београд 1984. [Résumé: M. Šakota, Trésor du monastère de Détchani, 445-457]

- Djurić, V. J. Icône du saint roi Stefan Uroš III avec des scènes de sa vie, Balkan Studies 24, Thessaloniki 1983, 373-401.

- Pantelić, B. The Architecture of Dečani and the Role of Archbishop Danilo II, Wiesbaden 2002.

- Popović, D. Shrine of King Stefan Uroš III Dečanski, Byzantium, Faith and Power (1261-1557), ed. H. C. Evans, New York 2004, 114-115. Šakota, M. Das Kloster Visoki Dečani, Dečani 1987.

Library, Manucsripts

- Благојевић, М. Када је краљ Душан потврдио Дечанску хрисовуљу?, Историјски часопис 16-17, Београд 1970, 79-86.

- Бубало, Ђ. Два прилога о Дечанским хрисовуљама, Стари српски архив 6, Београд 2007, 221-231. [Résumé: Đ. Bubalo, Deux contributions relatives aux chrysobulles de Dečani]

- Бубало, Ђ. Почетак треће Дечанске хрисовуље, Стари српски архив 6, Београд 2007, 69-82. [Abstract: Đ. Bubalo, Debut du troisieme chrysobulle de Dečani]

- Гроздановић-Пајић, М. Хиландар и рукописне књиге XIV века манастира Високи Дечани, Осам векова Хиландара, Београд 2000, 325-341. [Summary: M. Grozdanović-Pajić, Hilandar and fourteenth-century manuscripts from the Dečani monastery]

- Гроздановић-Пајић, М., Р. Станковић. Рукописне књиге манастира Високи Дечани II. Водени знаци и датирање, Београд 1995.

- Ивић П., В. Јерковић. Палеографски опис и правопис Дечанских хрисовуља, Нови Сад 1982.

- Ивић П., М. Грковић. Дечанске хрисовуље, Нови Сад 1976.

- Каталог Народне библиотеке у Београду. Рукописи и старе штампане књиге, ed. Љ. Стојановић и Љ. Штављанин-Ђорђевић, Београд 1982. [репринт]

- Мано-Зиси, К. Анагност Јован, хиландарски писар друге половине XIV века, Проучавање средњовековних јужнословенских рукописа, Београд 1995, 240-241. [Summary: K. Mano-Zisi, Anagnostes John, a Hilandar scribe of the second half of the fourteenth century]

- Медаковић, Д. Минијатуре Параклиса из Дечана, Старине Косова и Метохије 2-3, Приштина 1963, 101-115. [Résumé: D. Medaković, Miniatures du Paraklésis de Dečani]

- Мирковић, Л. Рукописни типици српскословенске рецензије, Типик архиепископа Никодима, књ. II, ed. Ђ. Трифуновић, Београд 2007, LIX-LX.

- Опис ћирилских рукописа Народне библиотеке Србије I, ed. Љ. Штављанин-Ђорђевић – М. Гроздановић-Пајић – Л. Цернић, Београд 1986.

- Опис ћирилских рукописа Народне библиотеке Србије I. Палеографски албум, ed. Љ. Штављанин-Ђорђевић – М. Гроздановић-Пајић – Л. Цернић, Београд 1991.

- Теодоровић-Шакота, М. Инвентар рукописних књига дечанске библиотеке, Саопштења 1, Београд 1956, 198-211. [Résumé: M. Teodorović-Šakota, Inventaire des livres manuscrits de la bibliotheque de Dečani]

- Хиландар у књигама, прир. Н. Мирков, Београд 1998, 175-179.

- Цернић, Л. Круг писара Јова, Археографски прилози 12, Београд 1990, 133.

- Цернић, Л. О атрибуцији средњовековних српских ћирилских рукописа. In: Текстологија средњовековних јужнословенских књижевности, Београд 1981, 335-360. [Résumé: L. Cernić, Sur l'atribution des manuscripts cyrillique serbes du moyen age]

- Чурчић, Л. Параклис Стефану Дечанском Јована Георгијевића из 1762. године. In: Српске књиге и српски писци 18. века, Нови Сад 1988, 152-177.

- Шакота, М. Два илуминирана рукописа из XVIII-XIX века у збирци манастира Дечана, Саопштења 4, Београд 1961, 57-66. [Résumé: M. Šakota, Deux manuscripts illuminés datant du XVIIIe et du XIXe siècle et faisant partie de la collection du monastère Dečani]

- Grković, M. The First Charter of the Dečani Monastery, Belgrade 2004.

- Kakridis, I. Codex 88 des Klosters Dečani und seine griechischen Vorlagen. Ein Kapitel der serbisch-byzantinischen Literaturbeziehungen im 14. Jahrhundert, München 1988.

- Kakridis, Y. Византијска античка и схоластичка традиција у српскословенским преводима дела Григорија Паламе и Варлаама Калабријског, Научни састанак слависта у Вукове дане 30/2, Београд 2002, 25-31.

- Kaleši, H., I. Eren. Čertnaest turskih fermana manastira Dečana, Glasnik Muzeja Kosova 10, Priština 1970, 305-344. [Summary: H. Kaleshi – I Eren, Fourteen Turkish fermans from the monastery of Dečani]

- Špadijer, I. Manuscript heritage. In: Hilandar monastery, ed. G. Subotić, Belgrade 1998, 115-124.