The Zograph Monastery of St.George

Regina Kojčeva, Ana Stojkova (Institute of Literature, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences)

History

Regina Kojčeva

The monastery of „St.George Zograph“ was one of the largest and most influential spiritual seats and cultural centres on the Balkans throughout the Middle Ages and the period of Ottoman rule. The monastery is situated in the northwest part of the Chalcidice peninsula, also known as Mount Athos, and is one the oldest among the monasteries.

Today the Zograph monastery is the only Bulgarian monastery at Mt. Athos. Its name comes from the legend of the miraculous painting of the image of St.George on the Phanouilian icon (see The Cult of St. George and the Zograph Monastery).

To this day there is no complete history of the monastery. Many of the sources have not been traced and studied in details. According to the legend, found in the Compiled Zograph Charter, the monastery was founded at the end of the 9th century or the beginning of the 10th by three brother of Bulgarian origin Moses, Aaron and Ivan Selima from Ohrid. In the lists of donors first comes Emperor Leo VI the Wise (887– 912). The inscription on the embossed silver cover on the Phanouilian Miraculous icon of St.George cites the year of the foundation as 898. In 972 , the painter George, considered to be the founder, signed the Typicon of Mt.Athos, issued by John I Tzimisces as Γεώργιος ‛ο ζωγράφος (Павликянов 2005: 17) A contract for a sale in Greek dated 980, is considered the earliest historical document for the existence of the monastery. The contract has been preserved in two copies in the Zorgraph archives. The second copy dated 1311 containing the signature in Cyrillic of Makarii hieromonk, Hegoumenos of Zograph. Judging by the two copies of the contract Zograph must have possessed certain land at last decades of 10th c. and had a statute of an independent monastery. Categorical proof of the Bulgarian character of Zograph monastery of St.George at Mt.Athos and its functioning comes as late as the 11th c on (Павликянов 2005: 17).

Information on the history of the monastery from its foundation to the beginning of the 13th century are absent. In the first half of the 13th century the Bulgarian King Ivan Assen II (1218–1241) became a donor to the monastery. The stronger ties of the monastery with the Bulgarian lands throughout this period point to the great authority and guidance of Zograph in the spiritual and cultural development in Bulgaria. It was namely to the Zograph monastic community that King Ivan Assen II turned for the choice of patriarch when the Bulgarian patriarchate was restored (Ioakim I, who prior to that had been a monk at Zograph). A number of the manuscripts preserved in the Zograph Library are examples of the reform of liturgical literature in 13th century ( for instance the Radomir Psalter, the Dobrijanov and Draganov menaia).

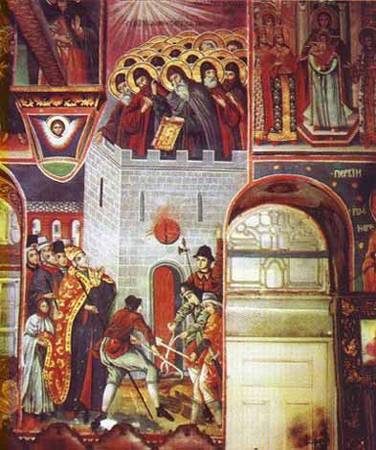

Owing to the resolute refusal to on the part of the community of monks at Zograph to abandon Orthodoxy, by accepting the Union between the Western and Eastern church, pronounced at the First Church Council at Lyon (1245), on October 10th 1275 the monastery was attacked by crusaders (Catalan mercenaries) who destroyed the monastery and burnt the 22 monks and 4 laymen brothers alive, in a defensive tower, raised by Ivan Assen II. The Narrative of the 26 martyrs from Zograph which probably originated at the begining the 14th century, states that the monastery plate from the times of the Bulgarian Kings Simeon, Petar and Samuil also burnt together with 193 books. Having suffered martyrdom, and fully destroyed, the monastery rejected to accept the ideas of the Union and support from Emperor Michael VIII (1223–1282). The monastery of Zograph recovered in 1289 when the new Byzantine Emperor Andronicus II Palaelogus confirned all its former rights and lands and donated means for a restoration of the destroyed buildings. Throughout the 14th century the Bulgarian rulers Ivan Alexander (1331– 1371) and Ivan Shishman (1371–1395) became generous donors.

No doubt Zograph was the main center of spiritual movement of the century in the Eastern Orthodox church, namely hesyhasm, as the lives of the central figures of Bulgarian hesychasts were linked to this monastery – the Bulgarian Patriarch Theodosius had formerly be a monk at Zograph and the last Patriarch St. Euthymios spent five years there (1365-1370) in the Selina tower, in the vicinity of Zograph, engaged in literary work (translations and editing liturgical works).

Throughout the Ottoman period Zograph remained the main spiritual seat and centre of cultural supporty for Christianity. In the 15th century St. Kosma of Zograph, the Bulgarian man of letters from Sofia, lived at Zograph, towards the end of the 16th century the Reverend Pimen of Zograph, painter of a wall painting at many a monastery in the Sofia area (cf. also The Cult of St.George and the Zograph monastery). From the 15th to the 19th century a number monks-men of letters worked at Zograph, copying liturgical works: Hierodeacon Malachia, Pop (priest) Manasii of Dryanovo, daskal (teacher) Pop Makarii, monk Gregory Iverion.

Under the difficult conditions of Turkish dominion, the Zograph monastery was supported by various donors. Towards the end of the 15th c. and the 16th c. donations came for Zograph from the Moldavian Voevod Stefan the Great (1457– 1504) and his successors. For over three decades Stefan the Great presented generous donations (cf. The Cult of St.George and the Zograph monastery). . After the destruction of the church of St.George by the Knights of Rhodes early in the 16thy century, the Moldavian rulers donated a considerable sum, rebuilding the church and redecorating it. Stefan the Greats successors presented the monasteries „Dobrovets“ and „Cyprian“ to Zograph.

Bulgarian and Russian were the donors of the Zograph monastery throughout the 17th and 19th century. Bulgarian pilgrims made donations not only to Zograph, but also to other monasteries at Mt. Athos. At the same time this was a period when gathering of alms by was a traveling monks (known as taxidiotes) was a current practice. In 1696, the Russian Emperor Peter I supported this practice, issuing a decree allowing taxidiotes from Zograph to gather alms in Russia every 5 years.

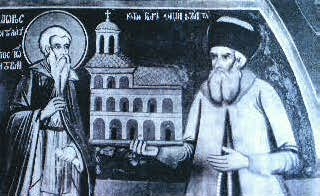

Hadži Vălcho (1705–1766), a brother of Paiissii of Hilandar and of the hegumenos of the monastery Hilandar Laurentios (his secular name was Lazar) was the main donor to Zograph and Hilandar. In the 50s and 60s In 1756 he gave money for the renewal of the chapel of the Hilandar monastery, and in 1758 he restored the entirely destroyed five-storey eastern wing with monks cells at Zograph, which is now known in his honour as the Bansko wing, or the Bansko quarters. It was his support which allowed in 1764 the construction of a small church of the Dormition of the Virgin, together with the church of ther Nativity of the Virgin at the Cherni vir skytos of the Zograph monastery. Hadži Vălcho’s portrait appears in gratitude in both monasteries.

In the 18th and 19th century Zograph became one of the centres of the Bulgarian National Revival Period. It was here that Paiissii of Hilendar completed his Istoria slavjanobolgarskaja in 1762, which is considered the starting point of the process of National Revival in Bulgarian literature. This is where the history was compiled, together with the Zograph History of Bulgaria.

The Zograph monoastery was an active element in the educational activities of the Bulgarian National Revival. In the 30s of the 19th century Archimandrite Anatolios and Hadži Victor , representative of the Zograph monastery met Vassil Aprilov, an eminent Bulgarian engaged with the promotion of modern Bulgarian education, in Russia. The outcome was the establishment of a modern secular school, where modern Bulgarian was taught in the curriculum, together with other secular subjects. This was realized by the mid 19th century at Zograph with highly qualified teaching staff, largely monks from the monastic fraternity. At the same time many monks from Zograph founded religious schools in various town in Bulgaria. Parallel to the activation of the Bulgarian National consciousness, after the mid 19th century, the Zograph monastery, until then inhabited by Bulgarian, Serbian and Greek monks, gradually became almost inhabited by Bulgarian monks.

In the period after the Liberation of Bulgaria from Ottoman rule at the end of the 19th century Zograph changed considerably and numbers of the Zograph fraternity of monks drastically was reduced. Today there are about 10 monks at Zograph.

Recently Zograph is engaged in energetic publishing of religious literature in Bulgaria. A number of books on moral guidance have been published, translations have been made into modern Bulgarian and of various works of the Holy Church Fathers, of the 12-volumes of Vitae of Dimitrii Rostovski, , with the addition of one more with the Vitae of the main Bulgarian saints.

Sources:

- Коцева, Е. Зографски манастир. В: Старобългарска литература. Енциклопедичен речник. Съставител: Д. Петканова. Второ преработено и допълнено издание. Велико Търново, 2003, с. 206 – 207.

- Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света Гора. Авторски колектив: Хр. Кодов, Б. Райков, Ст. Кожухаров. Със сътрудничеството на Ат. Ангелопулос и Ат. Каратанасис. Том I. София, 1985, с. 7 – 11.

- Нихоритис, К. Света Гора – Атон и българското новомъченичество. София, 2001, с. 36, 38, 40 – 41.

- Нихоритис, К. Славистични и българистични проучвания. Велико Търново, 2005, с. 138 – 140.

- Павликянов, К. История на българския светогорски манастир Зограф от 980 до 1804 г. София, 2005.

- www.pravoslavieto.com („Църковен вестник”, 2002 г., бр. 11)

- http://bg.wikipedia.org

- http://zograph.hit.bg

Wall paintings and architecture

Regina Kojčeva

In spite of the fact that Zograph is positively one of the oldest monasteries at Mount Athos, the vicissitudes of time have destroyed its Medieval architecture and only separate traces are found today. The monastery was built within stone wall in the shape of an enclosed rectangular area , with massive gateways and gates. The present-day buildings in the monastery are five-stories high (in some places six-stories high) and are comparatively recent – they were erected from the middle of the 18th century to the end of the 19th century on the foundations of earlier buildings. Of the wings with cells for the monks the southern one ( 1750) and the eastern one (1758) are the oldest ones. The northern and the western wing were built considerably later, in the second half of the 19th century

.Two churches in the monastery are situated in the center of the courtyard – the small one - the Dormition of the Virgin, built in 1764, and the main church of St. George, built in 1801. The iconostasies and wall painting in both are impressive. Wall paintings are both on biblical themes as well historical events: we find portraits of donors and images of a great number of Bulgarian saints, St.John of Rila, the brothers St.St. Cyril and Methodius, St. Nahum of Ohrid etc.

Within the monastery, in the churches themselves , between dwelling wings, as well as beyond the monastery lie another ten chapels, decorated with wall-paintings and wood-carved iconostases, such as those of St. John the Forerunner, St. Demetrios of Thessaloniki, the 26 Zograph Martyrs, St. Kosma of Zograph, the chapel of St.St.Cyril and Methodius and others. Specialists in wall paintings are particularly interested in the chapel of The Transfiguration of the Lord, at the Zograph konak in Kareia, the seat of the administration of Mt. Athos. The icons in the iconostasis dating from 1863 are the last work of the famous Bulgarian icon painter Zahary Zograph. Together with the chapels, a large number of Bulgarian sketes are scattered at the Mt. Athos, Chalkidiki Peninsula.

Alongside with churches and dwellings at Zograph there are also buildings with various functions. One of them is the octagonal marble structure for feast blessings with sacred water. The belfry at the eastern wing, was built in 1810 by Pavel Jovanovic. The clock-work mechanism with four faces, working to this day was placed on the tower in 1896. This clock was made by Todor Hadžiradonov, a self-taught mechanic from Bansko. Placing the clock was the conclusion of the shaping of the architectural complex. On the site of the old tower of the monastery, built by Ivan Assen II, and burnt down on October 10th 1275 a monument was raised in 1873 in memory of the 26 Zograph martyrs who died in the fire.

The principle building in Zograph is its main cathedral church of St.George the Victorious. The centuries of its history have still not been studied. According to the legend of the founding of the monastery, a church must have existed here towards the end of the 9th century or the beginning of the 10th century ( also cf. The Cult to St.George and the Zograph monastery). In history the Bulgarian king Ivan Assen II and the Byzantine Emperor Andronicus Paleologus are known to have rebuilt the church after devastation after wars. In the 15th century Zograph was overrun by barbarians and outlaws and was abandoned. It was only in 1502 that the Moldavian ruler Stefan the Great restored the old Medieval church ordered it to be redecorated. The new church was cruciform, with round semi-domes and the church has 6 lead covered domes : thee small one over the altar, two above the narthex and a large one in the middle.

About 1800 the church was demolished by the Zograph monastic community, to open ground for the site of a larger church. A plaque was placed above its entrance running as follows: „… създаде се от основанието този свещен храм на мястото на стария … с ктиторството на … проигумена Евтимия и господина проигумена Порфирия … в лето от Рождество Христово 1801.“ (… was erected, from the [time] of the foundation of this holy temple, on the site of the earlier one… with the donation of the Prohegumenos Euthymios and Prohegumenos Porphyrios… in the year of the birth of Christ 1801). The painter Nicephorus began to decorate the new church, completed in 1817 by master painter Mitrophanes, who did the main wall paintings. The scene of the death of the 26 martyrs of Zograph is particularly impressive. The magnificent iconostasis, completed in 1834, is a combination of Olt Testament and New Testament subjects , geometrical and plant motifs, and figures and phastastic figures. The wall paintings include a large number of donor’s portraits. The Byzantine Emperor Leo VI the Wise is depicted in the external narthex, as a “prime donor”, and Emperor Andronicus Paleologus, as a “second donor”, while the Bulgarian king Ivan Assen II and the Moldavian voevod Stefan the Great are depicted as those who restored the monastery. The image of the donor Hadži Vălcho, who had died 45 years prior to the construction of the new main cathedral is of particular historical importance. (cf. History of the Zograph Monastery).

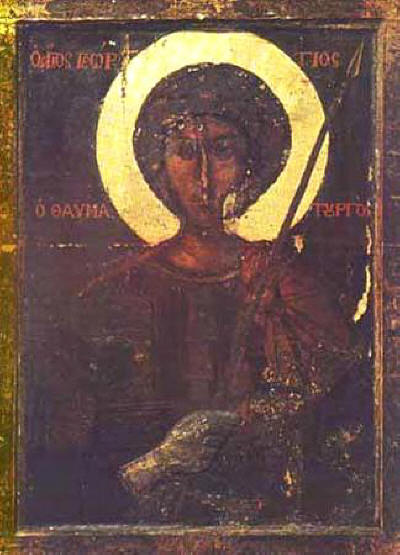

The three miraculous icons of St.George – the Phanouilian Miraculous icon, the Saracene Miraculous icon and the Moldavian Miraculous icon – are kept in the main monastery church. (cf. also The Cult to St.George and the Zograph monastery). The Phanouilian Miraculous icon is directly linked with the foundation of Zograph. Its silver embossed cover carries an inscription to the effect that the Bulgarian Royal and Patriarchal monastery was created in 898. In its stylistic features the Saracen icon can be attributed to the 13th century. It to has a cover, which is taken off when the icon is carried in feast processions beyond the monastery. The Moldavian icon, donated by Zograph in the beginning of the 16th century by the Moldavian ruler Stefan the Great, stands on a gilt wooden carved proskinitarion. Its silver cover was commissioned by Archimandrite Anatolius and was made in Russia in the 30s of the 19th century. The inscription on the cover runs as follows : St.George appeared before Stefan the Great, Voivod of Moldavia in 1484, after which Stefan the Great, voivod of Moldavia restored this holy Monastery of Zograph).

Many other valuable icons from the 14th–19th, some of them remarkable examples of Medieval and National Revival art are also kept in the churches and the museum collections of the Zograph monastery.

Sources:

- Божков, А., А. Василиев. Художественото наследство на манастира Зограф. С., 1981.

- www.pravoslavieto.com („Църковен вестник”, 2002 г., бр. 1, бр. 11. Препечатано с незначителни изменения от сп. euro2001.net, стр.38, бр.3, година XI, 2004 година)

- http://bg.wikipedia.org

- http://zograph.hit.bg

- http://www.geocities.com/arh_art/is38.html

- Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света Гора. Авторски колектив: Хр. Кодов, Б. Райков, Ст. Кожухаров. Със сътрудничеството на Ат. Ангелопулос и Ат. Каратанасис. Том I. София, 1985, с. 9 – 18.

- Коцева, Е. Зографски манастир. Старобългарска литература. Енциклопедичен речник. Съставител: Д. Петканова. Второ преработено и допълнено издание. Велико Търново, 2003, с. 206 – 207.

- Куев, К. Съдбата на старобългарските ръкописи през вековете. С., 1986.

- Нихоритис, К. Славистични и българистични проучвания. Велико Търново, 2005, с. 158–204.

- 1. Above all see Krumbacher 1911 on hagiographic works related to St.George in Byzantine literature (Krumbacher 1911). Halkin (1957: 669y-691y) enumerates passions (vitae et martyria), narratives of the birth of the saint, excerpts of vitae, homilies, visions and miracles, some of which are preserved in numerous versions. On hymnographic works cf. Petit 1926.

- 2.A translation of the Vita in modern Bulgarian with notes, see Иванова 1986: 398-408, 632-635.

- 3.A translation of the Miracle of the Dragon with a commentary and notes see Иванова 1986: 408-411, 635-637.

- Aufhauser, J. B. Das Drachenwunder des hl. Georg in der griechischen und lateinischen Überlieferung. Leipzig, 1911 (Byzantinisches Archiv, 5).

- Delehaye, H. Sanctus. Essai sur le culte des saints dans l’antiquité. (Subsidia Hagiographica 17), Bruxelles 1927, p. 74-121.

- Halkin, F. Bibliothecae Hagiographicae Graeca (BHG), 3 vols., 1957.

- Haubrichs, W. Georgslied und Georgslegende im frühen Mittelalter. Text und Rekonstruktion. Königstein im Taunus, 1979.

- Krumbacher, K. Der heilige Georg in der griechischen Überlieferung. München, 1911.

- Mazal, O. Zur hagiographischen Überlieferung und zur Ikonographie des heiligen Georg im byzantinischen Bereich. Codices manuscripti, 1990, 101-136.

- Paulus VI Papae Mysterii Paschalis (14 February 1969). General Norms for the Liturgical Year and the Calendar (February 14, 1969). – <http://www.catolicliturgy.com/index.cfm/FuseAction/Documentcontents/Index/2/SubIndex/38/DocumentIndex/97>

- Petit, L. Bibliographie des acoluthies grecques. Bruxelles, 1926, 86−89.

- Thomson, R.W. The Teaching of Saint Gregory, Cambridge Mass. 1970.

- Walter, Ch. The Origins of the Cult of St. George. Revue des Etudes Byzantines, 53, 1995, 295-326.

- Walter, Ch. The Warrior Saints in Byzantine Art and Tradition. Ashgate, 2003.

- Атанасов, Г. Свети Георги Победоносец. Култ и образ в православния Изток през Средновековието. Варна, 2001.

- Дончева-Панайотова, Н. Неизвестно (трето) Похвално слово за великомъченик Георги Победоносец от Григорий Цамблак. Търновска книжовна школа. Т. 6. Българската литература и изкуство от търновския период в историята на православния свят. Велико Търново, 1999, 19-38.

- Стара българска литература. 4. Житиеписни творби. Иванова, Кл. (Съст. и ред.). София, 1986.

- Мирчева, Е. Недамаскинови слова в новобългарските дамаскини от ХVІІ век. Велико Търново, 2001, 84−94.

- Стойкова, А. Произведенията за св. Георги в балканските кирилски ръкописи (Предварителни бележки). България и Сърбия в контекста на византийската цивилизация. Сборник статии от българо-сръбския симпозиум 14-16 септември 2003, София, 2005, 413-422.

- Стојкова, А. Чудо Светог Георгиjа са змаjем у Туманском апокрифном зборнику. Чудо у словенским културама. Уредио Деjан Аjдачић. Нови Сад, 2000, 109-125.

- <http://www.pravoslavieto.com> (Христо Темелски)

- <http://bg.wikipedia.org>

- <http://pravoslavie.domainbg.com/ps/2003/2/svgeorgi.html>

- <http://zograph.hit.bg>

- Ангелов, П. Отношенията между балканските държави, отразени в две грамоти от манастира Зограф от XIV в. Светогорска обител Зограф. Ред. В. Гюзелев, Т. Коев, П. Ангелов, Г. Бакалов. Т. 1. София, 1995.

- Аргиров Ст. Из находките ми в светогорските манастири Хилендар и Зограф. Периодическо списание на Българското книжовно дружество, 68, 1908, с. 219–23.

- Безобразов, П. Об актах Зографского монастыря. Византийский временник, 17, 1910.

- Бодянский О. М. Акт Зографского монастыря на Афоне 980–981 года. Чтения в Императорском Обществе истории и древностей российских при Московском университете, 1873, 3, с. 1–10.

- Божилов, И. Основаване на светата атонска българска обител Зограф. Легенди и факти. Светогорска обител Зограф. Ред. В. Гюзелев, Т. Коев, П. Ангелов, Г. Бакалов. Т. 1. София, 1995.

- Божков, А., А. Василиев. Художественото наследство на манастира Зограф. София, 1981.

- Болутов, Д. Български исторически паметници на Атон. София, 1961.

- Викторов А. Е. Собрание рукописей В. И. Григоровича. Москва, 1879.

- Викторов А. Е. Собрание рукописей П. И. Севастьянова. Москва, 1881.

- Григорович В. И. Очерк путешествия по Европейской Турции. Москва, 1877, с. 8–88.

- Гълъбов Г. Света гора. Българската света обител Зограф. София, 1930.

- Динеков П. Житието на Пимен Зографски. Известия на Института за литература, 2, 1954, с. 233–248.

- Дмитриев-Петкович, К. П. Обзор Афонских древностей. Приложение к VI-му тому Записок Императорской академии наук, 4, 1865.

- Дуйчев Ив. Центры византийско-славянского общения и сотрудничества. Труды Отдела древнерусской литературы, 19, 1963, с. 107–129.

- Енев, М. Атон – манастирът Зограф. Албум. София, 1994.

- Захариев В. Орнаменталната украса на Радомировия псалтир от библиотеката на Зографския манастир. Родина, 2, 1939, 2, с. 154–158.

- Зограф – славянобългарският манастир. Състав. П. Митанов, М. Енев. София, Музей на София, 1998.

- Иванов Й. Български старини из Македония. София, 1931.

- Иванов Й. Български старини из Македония. Фотот. изд. София, 1970.

- Иванов Й. История славеноболгарская, собрана и нареждена Паисием йеромонахом в лето 1762. София, 1914.

- Иванов, Й. Три писма от Зографския манастир. Избрани произведения, I, София, 1982.

- Иванова Кл. Зографският сборник, паметник от края на XIV век. Известия на Института за български език, 17, 1969, с. 105– 147.

- Ильинский Г. А. Грамоты болгарских царей. Москва, 1911.

- Ильинский Г. А. Значение Афона в истории славянской письменности. Журнал Министерства народного просвещения, 18, 1908, 11, с. 18–36.

- Ильинский Г. А. Рукописи Зографского монастыря на Афоне. Известия Русского археологического института в Константинополе, 13, 1908, с. 253–276.

- Ковачев, М. Български ктитори в Света гора. София, 1943.

- Ковачев М. Българско монашество в Атон. София, 1967.

- Ковачев, М. Зограф. Изследвания и документи. 1. София, 1942.

- Коцева, Е. Зографски манастир. Старобългарска литература. Енциклопедичен речник. Съставител: Д. Петканова. Второ преработено и допълнено издание. Велико Търново, 2003, с. 206–207.

- Куев К. Съдбата на старобългарските ръкописи през вековете. София, 1979, с. 33, 34, 62–70, 111, 118, 126, 188–190.

- Лавров П. А. Записка о путешествии по славянским землям. Известия Императорской академии наук, 3, 1895, 3, с. XXXVIII–ХLIII.

- Леонид архим. Историческое обозрение афонских славянских обителей: болгарской–Зографа, русской – Русика, сербской – Хилендаря. Херсон, 1867.

- Леонид архим. Славяно-сербские книгохранилища на Афонской горе. Чтения в Императорском Обществе истории и древностей российских при Московском университете, 1875, 1, с. 52–88.

- Лихачев Н. Рукопись, принадлежавшая патриарху Феодосию Тырновскому. Известия Отделения русского языка и словесности Императорской Академии наук, 10, 1905, 4, с. 312–319.

- Миклас, Х. Къде са отишли парорийските ръкописи? Търновска книжовна школа. Паметници. Поетика. Историография. Пети международен симпозиум. Велико Търново, 6–8 септември 1989 г. Велико Търново, 1994, 29–43.

- Мочульский, В. Н. Описание рукописей В. И. Григоровича. Летопись Историко-филологического общества при Императорском Новороссийском университете, 1, 1890, с. 53–133.

- Мошин, В. Зографские практики. Сборник в памет на П. Ников. Известия на Българското историческо дружество, 16–18, София, 1940.

- Нихоритис, К. Света Гора – Атон и българското новомъченичество. София, 2001.

- Нихоритис, К. Славистични и българистични проучвания. Велико Търново, 2005, с. 138–140.

- Кодов, Хр., Б. Райков, Ст. Кожухаров. Със сътрудничеството на Ат. Ангелопулос и Ат. Каратанасис. Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света Гора. Том I. София, 1985.

- Павликянов К. История на българския светогорски манастир Зограф от 980 до 1804 г. Свидетелствата на двадесет и седем неизвестни документа. София, Университетско издателство „Св. Климент Охридски”, 2005.

- Петкович К. Зограф, българска обител на Света гора. Цариградски вестник, 3, 23 май 1853, бр. 122.

- Райков, Б. Зографски манастир „Свети Георги”. Кирило-Методиевска енциклопедия. София. Т. I, 1985, с. 730–734.

- Светогорска обител Зограф. Ред. В. Гюзелев, Т. Коев, П. Ангелов, Г. Бакалов. София. Университетско издателство „Св. Климент Охридски”. T. I, 1995.

- Светогорска обител Зограф. Ред. В. Гюзелев, Т. Коев, П. Ангелов, Г. Бакалов. София. Университетско издателство „Св. Климент Охридски”. T. II, 1996.

- Светогорска обител Зограф. Ред. В. Гюзелев, Т. Коев, П. Ангелов, Г. Бакалов. София. Гутенберг. T. III, 1999.

- 75 години Ефория Зограф. Състав. Г. Бакалов, Г. Пенчев, К. Георгиева. София, Главно управление на архивите при Министерски съвет, 2001. Славяно-българската обител „Св. вмчк Георги Зограф”. София, Български художник, 1999.

- Стоилов, А. Своден хрисовул за историята на Зографския монастир. Сборник в чест на В. Златарски, София, 1925.

- Цветинов Г. Светогорският български манастир Зограф. Исторически очерк. София, 1918.

- Dujčev I. Chilandar et Zographou au Moyen âge. Хиландарски зборник. 1. Београд,1966, с. 21–30.

- Dujčev I. Le Mont Athos et les Slaves au Moyen âge. Le Millénaire du Mont Athos. 963–1963. Études et Mélanges. 2. Venezia, 1964, p. 121–144.

- Enev, M. Mount Athos - Zograph Monastery. Sofia, Kibela Publishers, 1994.

- Gelzer H. Sechs Urkunden des Georgsklosters Zografu. Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 12, 1903, p. 498–532.

- Mavrommatis, L. Andronikos II Palaiologos and the Monastery of Zographou (1318). Byzance et ses voisins. Mélanges à la mémoire de Gyula Moravcsik à l’occasion du centième anniversaire de sa naissance. Szeged, 1994.

- Mavrommatis, L. Le chrysobulle de Dušan pour Zographou. Byzantion, 52, 1982.

- Miklas H. Ein Beitrag zu den slavischen Handschriften auf dem Athos. Palaeobulgarica, 1, 1977, 1, p. 65–75.

- Nesev, G. Les monastères bulgares du Mont Athos. Études Historiques, 6, 1973.

- Regel W., E. Kurtz, B. Korablev. Actes de Zographou. Византийский временник. Приложение, 13, 1907, 1, с. 1–213.

- Tachiaos A. E. Mount Athos and the Slavic Literatures. Cyrillomethodianum, 4, 1977, p. 1–35.

- Tchérémissinoff, K. Les archives slaves médiévales du monastère de Zographou au Mont-Athos. Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 76, 1983.

- Μαυρομμάτης, Λ. Μεσαιωνικò ảρχει̃ο μονη̃ς Ζογράφου. ῎Εγγραφο πρώτου Δωροθέου. Άφιέρωμα στòν Νίκο Σβορω̃νο, I, Ρέθυμνον, 1986.

- Ван Вейк, Н. Еще раз о Зографском четвероевангелии. – Slavia, 1, 1922г., р. 215-218;`

- Срезневский, И. И. Исследования о древних памятниках старославянской литературы. СПб., 1852 г., с. 86;

- Срезневский, И. И. Известие о глаголическом четвероевангелии Зографского монастыря, ИИАН по ОРЯС, 4, 1855 – 1856 г., с. 369-377;

- Срезневский, И. И. Из обозрения глаголических памятников. – Известия императорского археологического общества, 4, 1863 г., 2, с. 93-119;

- Срезневский, И. И. Календарные приписки кириллицей в глаголических рукописях. 2. Из Зографского евангелия. – В: Сведения и заметки о малоизвестных и неизвестных памятниках. СПб., 1875 г., (СОРЯС, 1, 1867 г., 6, с. 69-76);

- Ганка, В. Начала священного языка славян. Прага, 1859 г., с. 48;

- Каринский, Н. Хрестоматия по древнецерковно-славянскому и русскому языкам. 1. Древнейшие памятники. СПб., 1904 г., 3, с. 229;

- Грунский, Н. К. Зографскому евангелию. – СОРЯС, 83, 1907 г., 3 с. 1-51;

- Ягич, В. Глаголическое письмо. – В: Енциклопедия славянской филологии. 3, СПб., 1911 г., с. 51-262;

- Van Wijk, N. O prototypie cerkiewnowslowianskiego Codex Zographensis. – RS, 9, 1921, p. 1-14;

- Van Wijk, N. Zu den altbulgarischen Halbvokalen. 4. Der Umlsut der Halbvokale im Codex Zographensis. – ASPh, 39, 1925, p. 15-43;

- Van Wijk, N. Geschichte der altkirchenslavischen Sprache. 1. Berlin und Leipzig, 1931, p. 256;

- Загребин, В. М. О происхождении современного оклада Зографского евангелия. – Palaeobulgarica, 2, 1978 г., 1, с. 66-73;

- Добрев, Ив. Към въпроса за прототиповете на старобългарския глаголически тетраевангелски текст Codex Zographensis. – БЕ, 17, 1967 г., 2, с. 144-146;

- Добрев, Ив. Палимпсестовите части на Зографското евангелие. – ККФ 2, с. 157-164;

- Добрев, Ив. Къде е писано Зографското евангелие и къде е странствувало то из западнославянски земи. – БЕ, 22, 1972 г., 6, с. 546-549;

- Гранстрем, Е. Описание русских и славнянских пергаменных рукописей. Ленинград, 1953 г., с. 77 (глаг. 1);

- Илчев, П. Към първоначалното състояние на графическа писмена система. ЕЛ, 24, 1969 г., 5, с. 29-39;

- Лавров, П. Кирило та Методiий в давньо-слов'янському письменствi. Киев, 1928 г., с. 340-342;

- Огиенко, I в. Пам'ятки старо-слов ' янськоï мови X – XI вiкiв. Варшава, 1929 г., с. 494;

- Jagić, V. Studien über das altslovenisch-glagolitische Zographos-Evangelium. – ASPh, 1876, p. 1-55; 2, 1877, p. 201-269;

- Jagić, V. Quattuor evangeliorum Codex glagoliticus olim Zographensis, nunc Petropolitanus. Berolini, 1879, p. 224 (phototypic ed. Graz, 1954);

- Leskien, A. Zograph. Evang. Marc. 1.6. – ASPh, 2, 1877, p. 191-192;

- Leskien, A. Die Vokale Ъ, Ь in den Codices Zographensis und Marianus. – ASPh, 27, 1905, p. 321-349;

- Geitler, L. Die albanesischen und slavischen Schriften. Wien, 1883, p. 213;

- Wiedemann, O. Beiträge zur altbulgarischen Konjugation. St. Peterburg, 1886, p. 157;

- Kurz, J. Nékolik poznámek k staroslovanskemu ctveroevangeliu Zografskému. – LF, 50, 1923, p. 229-232;

- Kurz, J. K Zografskému evangeliu. – Slavia, 9, 1930, p. 683-696; 11, 1932, p. 385-424;

- Diels, P. Altkirchenslavische Gramatik. 1. Heidelberg, 1932, p. 8;

- Moszynski, L. Ze studiòw nad rekopisem Kodeksu Zografskiego. Wroclaw, 1961, p. 132;

- Moszynski, L. Warstwy jezykowe w Kodeksie Zografskim. – Z polskich studiow slawistycznych, 2, 1963, 1, p. 237-265;

- Moszynski, L. Jezyk Kodeksu Zografskiego, 1. Wroclaw, 1975, p. 287;

- Moszynski, L. Kanony Euzebiusza w glagilskim rekopiste Kodeksu Zografskiego. – Slovo, 25-26, 1976, p. 77-119;

- Galabov, Iv. Onomastischen aus dem Zographensis. – In: Serta slavica in memoriam Aloisii Schmaus. München, 1971, p. 171-178;

- Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 281, с. 141

- Lavrov, P. Les Feuilles du Zograph. - RES, 6, p. 5-23;

- Lavrov, P., A. Vaillant. Les Regles du Saint-Basil en vieux slave: Les Feuilles du Zograph. - RES, 10, 1930, p. 5-35;

- Dolobko, M. La Langue des Feuilles du Zograph. – RES, 6, 1926, p. 24-38;

- Miklas, H. Ein Beitrag zu den slavischen Handschriften auf dem Athos. – Palaeobulgarica, 1, 1977, p. 65-76;

- Минчева, Ангелина. Старобългарски кирилски откъслеци. Издателство на БАН, София, 1978 г., с. 39-45;

- I.д.2; Кодов, Райков, Кожухаров 1985: № 53, с. 99-100;

- Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 14, с. 35

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год.

- Илински 40, опис 53, с. 99-100;

- Лавров, П. А. Альбомъ снимковъ съ Кирилловскихъ рукописей болгарскаго и сербскаго письма П. А. Лаврова, Петроград, 1916 год., с. 116;

- Иванов, Й. Българските старини из Македония. 1 издание, София, 1980 год.; 2 издание, София, 1931 год. (фототипно издание, 1970 год.), БСМ², с. 233-234;

- Петров, П.; Гюзелев, В. Христоматия по история на България. Том I, II, София, 1978 год. ХБИ, II, с. 412;

- Edition of the scribal note: П. А. Лавров. Запись в Минея № 6 (32) от Одеского собрание рукописей В. И. Григоровича;

- Куев, Куйо. Съдбата на българската ръкописна книга. 1986 год., с. 69, № 3;

- Кожухаров, Стефан; Божилов, Иван. Българската литература и книжнина през XIII век. изд. “Български писател”, София, 1987 год., с. 307;

- I.e.9. Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 54, с. 52

- Иванов, Й. Българските старини из Македония. 1 издание, София, 1980 год.; 2 издание, София, 1931 год. (фототипно издание, 1970 год.), БСМ², с. 359-367, 387-390, 424-431;

- Петров, П.; Гюзелев, В. Христоматия по история на България. Том I, II, София, 1978 год. ХБИ, II;

- Кожухаров, Стефан; Божилов, Иван. Българската литература и книжнина през XIII век. изд. “Български писател”, София, 1987 год., с. 305, ill. 7

- I.e.7. Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 53, с. 52

- Успенский, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 88, с. 267, № 88;

- I.д.13; Кодов, Райков, Кожухаров 1985: № 1, с. 27-29;

- Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 59, с. 54-55

- Кожухаров, Стефан; Божилов, Иван. Българската литература и книжнина през XIII век. изд. “Български писател”, София, 1987 год., с. 303;

- Успенский, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год.

- Илински 47, Опис 1, с. 27-29;

- Edition of the scribal's note and its translation into Bulgarian: Дуйчев, Иван. Из старата българска книжнина, СБК, II, с. 280, София, 1944 год.;

- Кодов, Христо; Кожухаров, Стефан; Райков, Божидар. Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света гора, том 1, Държавно издателство “Свят”, София, 1985 год., с. 29;

- I.д.4. Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 39, с. 46

- Успенский, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илинский 74;

- I.д.2. Кодов, Райков, Кожухаров 1985, № 54, с. 100-102;

- Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 49, с. 50

- Успенский, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 41, Опис 54, с. 100-102;

- Срезневский, И. И. Сведения и заметки о малоизвестных и неизвестных памятниках. СПБ. LXXXI; 1979 год., с. 34-35;

- Викторов, А. Е. Собрание рукописей П. И. Севастьянова. Москва, 1881 год., с. 42;

- Успенский, П. Второе путешествие (книг в Болгарии по святой горе). Афонской, Москва, 1880 год., с. 150;

- Сырку, П. К истории исправления книг в Болгарии в XIV веке. Вып. I. Время и жизнь патриарха Евфимия Терновского. СПБ, 1898 год., с. 452;

- I.б.3. Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 3, с. 30

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 41, № 152, с. 273;

- Лавров, П. А. Альбомъ снимковъ съ Кирилловскихъ рукописей болгарскаго и сербскаго письма П. А. Лаврова, Петроград, 1916 год., № 35;

- Викторов, А. Е. Собрание рукописей П. И. Севастьянова. Москва, 1881 год., 95 (№ 22);

- Григорович. Очерк, 56 (№ 31);

- Порфирий. 157 (№ 39);

- I.г.9. Кодов, Райков, Кожухаров 1985, № 21, с. 58-59;

- Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 40, с. 46-47

- Ягича, И. В. Енциклопедия Славянской филологи. Альбомъ снимковъ съ Кирилловскихъ рукописей болгарскаго и сербскаго письма от П. А. Лавров, Петроград, 1916 год., № 26 (има илюстрация);

- И. И. Срезневский. Древние славянские памятники юсоваго письма. СПБ, 1868 год., с. 123;

- И. И. Срезневский. Древние славянские памятники юсоваго письма. СПБ, 1868 год., с. 348-349;

- Христо Кодов, Стефан Кожухаров, Божидар Райков. Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света гора, т. 1; държавно издателство “Свят”, София, 1985 год., с. 58-59, опис 21;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинополe. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински, с. 57;

- I.в.1. Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 24, с. 39-40

- Христо Кодов, Стефан Кожухаров, Божидар Райков. Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света гора, т. 1; държавно издателство “Свят”, София, 1985 год., с. 65-66, опис 28;

- Караджова, Д. Археографски приноси за ръкописно хранилище на Зографския манастир на Света гора. – Археографски прилози, 17, 1995 год., с. 230-231;

- Турилов, А. А. Старобългарска литература, с. 33-34;

- II.д.6

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински, с. 274, № 171, опис IX;

- Каталог 107, с. 77;

- Климентина Иванова. Зографският сборник..., - ИИБЕ, 1960 год.;

- II.б.5.

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински, с. 274, опис VI - Жития, № 164;

- Каталог 83, s. 65-66;

- Николова, Св. Патеричните разкази..., с. 147-384, 385-386;

- I.д. 14; Кодов, Райков, Кожухаров 1985, № 23, с. 60-61;

- Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 60, с. 55

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински, с. 51-52, опис 15;

- II.в.5. Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 96, с. 71

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински, с. 275, опис Х, № 181;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински, с. 273, опис IV, № 157

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 184, с. 276, опис ХI - Сборники, № 157

- Каталог 90, с. 68;

- Б. Христова. Ръкописите от XIV век в библиотеката на Зографския манастир. – Старобългарска литература, с. 28-29, 1994 год.;

- I.и.3. Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 168, с. 103

- Куев, Куйо. Съдбата на българската ръкописна книга. Изд. “Наука и изкуство”, София, 1986 год., второ издание, с. 44, № 8;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 167, с. 274, Каталог 115, с. 81

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 105, с. 269, Каталог № 106, с. 76;

- Стоилов. Преглед, 136 (№ 15);

- II.б.1

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 89, с. 267, Каталог № 62, с. 56.

- Стоилов. Преглед, 134-135 (№ 10);

- III.a.7. Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 132, с. 89-90.

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 137;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 89, с. 270, Каталог № 120, опис 10;

- Викторов. с. 94;

- Порфирий, с. 151 (№ 21).

- Антонинъ, Заметки поклонника о Св. Гора, 329;

- Сырку. Къ истории. I, 2, I;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 89, с. 270, Каталог № 120, опис 10;

- Каталог 46; Й. Иванов, № 10, с. 238 (publieshed the scribal note from XIV century - 1397;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 161, с. 273, Каталог № 161, опис V; Лествичник, XVI век;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 166, с. 274, Каталог № 166, опис VI - Жития;

- Каталог 94;

- Климентина Иванова. Малки бележки върху ръкописи от библиотеката на Зографския манастир. – Старобългарска литература, с. 28-29, 1994 год.;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 77, с. 266;

- Каталог 215;

- Д. Караджова. Археографски приноси…, Археографски прилози, 17, с. 213;

- Христо Кодов, Стефан Кожухаров, Божидар Райков. Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света гора, т. 1; държавно издателство “Свят”, София, 1985 год., с. 70-71;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 151 (Особоя переделка, 293 листа, в Опис IV – Историческа книга Зонары, II г 4, с. 272, XVII век);

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 173, с. 274, опис IX – Прологи;

- Каталог 109;

- Иванова, Климентина. Малки бележки върху ръкописи от библиотеката на Зографския манастир. – Старобългарска литература, 1994, с. 28-29, 797-799;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 32, с. 80-81, опис 39;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 29, с. 96-97, опис 50;

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинопола. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 179, с. 275, опис IX – Прологи;

- Кодов, Райков, Кожухаров № 5, с. 34-35;

- Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 171, с. 104

- Христо Кодов, Стефан Кожухаров, Божидар Райков. Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света гора, т. 1; държавно издателство “Свят”, София, 1985 год., с. 34-35;

- II.б.1; Кодов, Райков, Кожухаров 1985: 10, с. 44-45;

- Райков, Кожухаров, Миклас, Кодов 1994, № 79, с. 63-64

- Успенски, Ф. И. Известия русскаго археологическаго института въ Константинополе. Том XIII, София, Държавна печатница, 1908 год. виж Илински 59, с. 264, опис I, 4;

- Христо Кодов, Стефан Кожухаров, Божидар Райков. Опис на славянските ръкописи в библиотеката на Зографския манастир в Света гора, т. 1; държавно издателство “Свят”, София, 1985 год., с. 44-45, опис 10;

- Иванов, Й. 2 издание, с. 254, № 64;

- Enev, M. Mount Athos – Zograph Monastery. Sofia, Kibela Publishers, 1994.

The Library of the Zograph Monastery

Regina Kojčeva

One of the most remarkable treasures of the Zograph Monastery is its library, which is of particular interest for scholars.

Information on the acquisition of manuscripts at the Zograph library is scant. Part of the codices preserved indicate that the monastery was a key institution in the reform of liturgical books, which occurred in the 13th and 14th century. The last Bulgarian patriarch, St. Euthymios of Tarnovo, had stayed in 1365-1370 in the Selina tower, near Zograph, personally took part in this reform. Part of St. Euthymios’ translations were done during this stay. Three of his most valuable works and translations – the Zograph Scroll, The Service book of Patriarch Euthymios and the Zograph Myscellany, dating from the end of the 14th century. Alongside with the information contained in these manuscripts from this period of the history of the Zograph library, a letter has also been preserved, reporting that the Bulgarian patriarch St.Thedosius had sent a Gospel, written in 1348, a copy of the Pandects of Nikon of Montenegro, and a copy of the Vita of St.Nicolas to Zograph (so far the copy of the Vita has not been found).

Apparently the authority of the Zograph library in those times was high and in the subsequent 15th and 16th century it became the practice of sending valuable codices to Zograph from all monasteries in the interior of the Balkans for safe keeping. At the sam time literary work at Zograph also continued. The names of a number of Zograph scholars from the 15th to the 19th century have cone down – Hierodeacon Malahia, Pop Manasii of Dryanovo, daskal (teacher) Pop Makarii, monk Gregory Iverion etc. Literary work at Zograph flourished in the 18th century, as is evident from the great number of manuscripts from the same period preserved there. Paiisii’s Istoriya Slavyanobolgarskaya dates from the same period . Its original dated 1762 is kept to this date at the Bulgarian monastery in Mt.Athos. Literary traditions remained alive in later periods. Thus 1923 monk Panaret of Zograph composed a liturgy for the miraculous icon of the Holy Virgin-of-the-Warning , and for the Twenty-six martyrs from Zograph, which was discovered and published in 2005 by Konstantinos Nihoritis, the Greek scholar in the field of Bulgarian studies.

Alongside with the acquisition of valuable manuscripts the Zograph library also suffered considerable losses. We know from the narrative for the 26 martyrs that 193 books, kept in the tower were lost in the fire of 1275. (cf. History of the Zograph Monastery). Quoting Archimandrite Leonides’ narrative in his article dated 1867 Историческое обозрение афонских славяских обитателей: болгарской – Зографа, русской – Русика, сербской – Хилендаря, during the Greek upraising of 1821–1830 , the Turks destroyed, burnt or sold manuscripts from Zograph, Today it is impossible to establish which codices were destroyed at the time, as no catalogue of the Zograph manuscripts existed at the time.

Unfortumately the first scholar to visit the library of Zongraph also caused loss to its collection. The Russian Victor Grigorovič, who visited Zograph in 1844–1845 twice, secretly took away with him folia from valuable manuscripts (5 folia of a trebnik (prayer-book) from the 14th c.; 6 folia of a Lenten triodion from the 14th c.; 2 folia from the Draganov menaion (Zograph Trephologion) from the 13th c., which contains the synaxarion Vita of St.John of Rila; 2 folia from a Full menaion for June etc). At the same time another Russian scholar – bishop Porfirii Čigirinskij (K. Uspenskij), who visited Mt.Athos in the 50s took away folia from 26 manuscripts from Zograph. These fragments of MS were bought by the Imperial Public Library at St.Petersburg (today the National Library in Sankt Petersburg), where they are to this day.

The Russian archeographer and collectioner P. I. Sevastianov also visited Mt Athos in the 50s of th 19th century.With the permission of the monastic fraternities he made a collection of manuscripts, including MS from Zograph, which today is kept in the collection of the State Russian Library in Moscow. The Bulgarian monastic fraternity sent the most valuable book in its collection – the Glagolithic Zograph Gospel as a present to the Russian Emperor via Sevastianov on September 8th 1860, which today belongs to the the National Library in Sankt Petersburg.

The poor care for old codices also affrected the manuscript collections of Zograph. In his article 1903 „Преглед на славянските ръкописи в Зографския мънастир“ (Survey of the Slavonic Manuscripts in Zograph Monastery) A.P. Stoilov remarks that in 1866, when part of the collection was being bound by the then librarian father Neftilin, the original covers were thrown away, many of the folia mixed up, and the cutting in many cases affected the body of the text and fully had destroyed some marginal notes.

Academic interest towards the survived codices in the library of the Bulgarian monastery in Mt.Athos began simultaneously with the removal of entire manuscripts and parts of them from Zograph in the mid 19th century. The first report of the existence of the Zograph Glagolithic Gospel from the 10th c came from Antun Mikhanovic, the Austrian consul at Thessaloniki. Over the 1848–1908 period various studies, lists, discoveries of Zograph manuscripts and publications of texts were the work of V.Grigorovic, P.I. Sevastianov, Arhimandrite Leonid, P. Uspenskij, P.A.Lavrov, G.A Ilinskij and th Bulgarian scholars K.D. Petkovič, A.P. Stoilov, St.Argirov, and J. Ivanov. Here we should mention the discovery of folia from Zograph from the 11th c. (containing a fragment of the monastic rules of St.Basil trhe Great), by P.A. Lavrov, together with a large number of works in Old Bulgarian (among them the earliest Slavonic Vita of St. Nahum of Ohrid, compiled in the 10th c.) by J. Ivanov, brought out in his work „Български старини из Македония“ (Bulgarian antiquities from Macedonia), 1908. This book reveals the full depth of the academic value of the manuscript collection of the library at Zograph.

The first full list of the Slavic collection of manuscripts at Zograph was done by the Bulgarian scholars H. Kodov, B. Rajkov, S. Kožuharov with their Greek colleagues A. Angelopoulos and A. Karatanasis and was published in 1985. Nine years later (1994) the same authors together with their colleague, Austrian specialist in Bulgarian studies, Heinz Miklas published a full brief catalogue of the manuscripts, accompanied with reproductions.

As a result of these studies it has been established that today the library at Zograph possess 126 Greek manuscripts, 388 Slavonic manuscripts and approximately 10000 printed books. The manuscripts are parchment and paper. The earliest Slavonic monument are the Zograph folia from the 11th c. Mentioned above, and the latest manuscripts are from the 20th c. The Slavic manuscript collection includes Bulgarian, Russian, Serbian, Wallachian-Moldavian codeces. The collection is kept in the upper storey of the monastery library. Many of the manuscripts need restoration and conservation.

Sources:

St. George the Victorious

Ana Stojkova

One of the most popular Christian saints, saint protector of the Zograph monastery at Mount Athos. Martyr, at Lydda (Diospolis) in Palestine 303 during the reign of Diocletian.

The earliest epigraphical data for his veneration come from Syria, Mesopotamia and Egypt and date from the 4th century, the earliest preserved witness of hagiographic text, the so called Vienna Palimpsest fates from the 5th–6th century. In the 6th century there already is mention of his grave at Diospolis, as a place of pilgrimage. Owing to battles against the Saracens won with his support, St.George early began to be venerated throughout the entire Eastern Mediterranean. Non less than six churches have been dedicated to St.George in the Byzantine capital. The oldest one, together with that raised over the grave of the martyr in Lydda the legend attributes to Constantine the Great. Nevertheless there can be no doubt that the first Christian emperors dedicated churches to the saint. In the 6th century Justinian built the church of St.George in Armenia Minor, emperor Mauritius built another in Constantinople. The largest church after St.Sophia in Constantipole , built in the 11th century, in the Mangana quarter, was also dedicated to St.George. A number of hagiographic, hymnographic and rhetorical works arose in the course of his veneration in the church in Greek over the centuries. At an early stage the saint began to be venerated in Weestern Europe as well. As early as the 6th century St.Gregory of Tour mentions St.George as a high venerated saint in France. Instructions of Pope Gregory the Great have come down for the renewal of a church, dedicated to St.George. The earliest narrative of the Martydom of St.George was transdlated in Latin very early and penetrated into West-European Medieval literature. The popularity of the cult of St.George considerably grew only after the crusades.

Amidst the Slavs the cult of the martyr appeared together with their baptism. Early data are known on churches , dedicated to St.George in Prague (920) and Kiev (1053). During the 10th and the 11thg century the rotunda – the church of St.George in Sofia existed. The earliest mention of St.George in Orthodox Slavic sources is in the calendar of the Glagolithic Codex Asemani, an Old Bulgarian manuscript from the second half of the 10th century and the beginning of the 11th century. There is ground to suppose that St. George was among the first Christian saints, introduced in the feast calendar of the newly baptized Bulgarian after 864. Its increase in popularity over the subsequent centuries amidst Orthodox Balkan slavs can be seen in the great number of churches the lands of Bulgarians and Serbians, the great number of literary works, translations and original works, dedicated to St.George by southern Slavic men of letters, from the evolution of his Feast day, April 23, as one of the major events in the traditional popular calendar of socially significant feast days, his veneration as patron of shepherds and agriculture and even the use of his name as one of the most popular anthroponyms to this day.

According to the church legend St. George was born in Capadokia, in an aristocratic Christian family. After the death of his father George went together with his mother to Palestine. He became a legioneer and quite young rose to the rank of tribune . When Emperor Diocletian began hos persecutions against the Christians, St.George abandoned his high position, gave away his possessions to the poor and declared himself being a Christian. He was locked up, questioned and tortured, to force him to give up his Christian beliefs. Torture failed to break his belief and he was beheaded on April 23rd 303.

St.George did many miracles , the most famous of them his victory over the dragon. Most of the miracles occurred after his death ands were the result of prayers of people in need.

The issue of the existence of St.George remains subject of discussion, as the historical data about him are unrealibale or are difficult to be associated with him (Delehaye 1927; Haubrichs 1979; Walter 1995). This is why in 1969, following the reform undertaken by Pope Paul VI (Paulus VI Papae 1969), he was removed from the official Catholic feast calendar, as his veneration in separate local churches. In 1975 his name appeared again in the Principal Roman Calendar.

The Feast of St.George was venerated on April 23rd ( the date of his death according to the Torture). In some Orthodox countries (Russia, Serbia, Macedonia) it is celebrated on May 2nd (according to the Julian Calendar). In the Bulgarian church calendar, which corresponded to the Gregorian calendar, May 6 remained as an exception, as the 23rd sometimes is before Easter (during the Greast fasting) and hence it could not be celebrated according to the tradition. The consecration of the church of St.George was done on November 3rd at his grave at Lydda (the Palestinean Feast). November 26th was an old feast of St.George at Constantinople, connected with the consecreation of the church of St.George „under the Cypress-trees“, which was kept in the southern Slavic manuscript tradition. The church of St.George in Kiev was was consecrated on the same day in 1053; in the Russian tradition November 26 is noted as the day of the Miracle with the Dragon.

The veneration of St.George over the centuries was connected with the creation an enormous number of literary works. Over 40 hagiographic works, preserved in the numerous versions and tens of hymnographic works occur in Byzantine literature1. The oldest Torture of the Saint, preserved partially in the Viena Palimpsest (5th–6th c.) is the basis of all later redactions and edited versions. This early Greek Vita, is also an edited older text filled with a long narrative of the tortures of the saint, written in the spirit of the Hellenistic novel. Here George is tortured by 72 kings, led by King Dadianos, he drinks poison, which has no effect, he is cut into pieces three times, buried deep in the ground and burnt, and every time brought back to life by the Lord, who appears in person, to encourage him to stand for faith. People , long dead, are brought back to life and baptized, many, among them queen Alexandra, become Christians, idols are broken, green shoots come from chairs and beams, and flourish, the deal ox of an old woman come back to life. In the end, without rejecting his faith, George is taken out of town and beheaded. Thunder and a powerful earthquake accompany his death.

Probably namely this text was mentioned at the end of the 5th century in the so called Decretum Gelasianum, an Index of forbidden books. Nevertheless the ban did not stop the wide spread in the subsequent centuries. Evidently contradictions in the contents with the formulated dogma of the day and Chriatian postulates caused the creation of a great number of revisions and versions, which aimed at changing the text in the line of the official Christian doctrines. One of the most common ones was written by Theodore Daphnopates, another by Nikita David Paphlagones, whose text Simon Metaphrastes also edited and included in his menologion. Later brief summaries appear, copied in synaxaria. Rhetorical and poetical edited versions of the vitae and over 10 encomia also are found in Byzantine literature. A large number of hymnographic works dedicated to St.George – kanons, stichera, kontakia and oikoi, troparia, prayer kannons, written by Joseph the Hymnographer, St.Cosmas the Hymnographer, the Bishop of Maiuma and St.Theophanes the Branded. Specific phenomena in hymnography coincided with the Rezurrection, composed by Patriarch Philoteios. (14th c.).

Numerous miracles after the saints death appear in the late Byzantine period, attributd to him, which spread separatetly or are gathered together in cycles. A considerable number of miscellanies containing only works dedicated to the saint have come down to us. As a rule thy were commissioned for separate monastery whose patron St. George was.

The Miracle with the Dragon (Aufhauser 1911) assume a special place among literary works dedicated to St.George. It is a narrative of the feat of the saint, who saves a maiden, the daughter of a pagan King, by overwhelming the monster through the sign of the cross and then baptizes the pagans. Although appearing much later than the Vitae and the martyrdom – probably 11th century, this work won great popularity and throughout the subsequent centuries the image of the saint was inadvertently associated with the victory over the dragon. The Miracle with the dragon widely spread in many redactions and versions, and together with th numerous wall paintings and icons exerted its influence over the idea of the image of the saint throughout the entire Christian world.

Probably trhe cult to St.George was among the earliest to be also included in the Old Bulgarian feast calendar. Besides the early mention in calendars, copies of many hagiographic and hymnographic works dedicated to St.George (Стойкова 2005) have been preserved. There is ground to consider that the oldest „apocryphic“ martyrdom of the saint (BHG 670)2in the early period – had been translated in the end of the 9th century and the beginning of the 10th century. The so called Pogodinov index (list of non-cannonical books) composed in 10th–11th c. mentions the existence such a Vita. Two redactions and about 10 copies in the South Slavonic manuscript tradition, included in Reading Menaia of the Old Version (pre-Metaphrastes), one of them preserved in the Croatian fragments of Vrabnitza ( from the second half of the 13th century) are also known. Another Vita (BHG 670g), translated into Old Bulgarian, also probably in the Old Bulgarian period, with a narrative about the parents of George – the pagan Gerontius and the Christian Polychronia – occurs in Bulgarian and Serbian copies. Another two Vitae of St.George, also appearing in the so called „novoproizvodni“ miscellanies (of the New Version, followed the Jerusalem Typikon) were written by Bulgarian monks from Mount Athos and Tărnovo. These miscellanies also include the so called Martyrdom of Pasikratos (BHG 671, 672)and the copy of the Vita of Nikita David Paphlagonia, which was revised and included in the Menologion of Simeon Metaphrastes(BHG 676b). The manuscript tradition is also preserved in copies of two synaxarion notes of Vitae from the Non-versesified and Versified Prolog. Also three miracles of the saint (The column of the widow, The captured youth from Mitilene, The fried eggs) usually are included in the Versified Prolog. As a complex they have their place in the menaion of New version (follows the Jerusalem Typikon) after the 6th song of the cannon. The miracle of the dragon occurs in two versions. Almost all later copies known today in Balkan Cyrillic MS (Стойкова 2000)3 are drawn from the version included in the Dragolov miscellany from the third quarter of the 13th century. Several later copies from another vesrsion, spread chiefly in archaic damascenes are an exception and probably reflect Russian literary influence in the 16th c.

Besides the Three Miracles of St.George in the Versified prolog another tyhree are presereved: the Miracle about the Oxen of Theophistos, About the son of Leo the Paphlagonian, the Icon of the saint, The Demon, all of them included in later miscellanies. It is noteworthy that there are almost no translated Homilies for St.George in the South Slavic literatures. The only copy of the Homily of St.George by Andreas of Crete is in the Rila Panegyric by Vladislav the Grammarian of 1479. Nevertheless in the two miscellanies of the New Version encomia from the 14th– 15th century there are original Homilies for St.George, written by Gregory Tzamblak and recently a third Homily for St. George, also attributed to this Old Bulgarian writer (Дончева-Панайотова 1999). Also late copies of the translated Homily for the renewal of the Church of St.George at Lydda (November 3rd) by Arcadius of Cyrus (BHG 684). In the 17th and 18th century translations of Damascenes at the end of the 16th century in popular dialectal Bulgarian led to a further growth in the popularity of St.George. In the original text of his anthology „Thesauros“ Damascene Studite included his version of the Metaphrastian Vita of the Saint, the Three Miracles of the Versified Prolog, and the Miracle for the Son of Leo the Paphlagonian. The briad distribution of these books greatly contributed to the popularization of the cult of the martyred saint and the miracles in the National Revival Period.

In Bulgarian folklore St.George is venerated as the protection of the rebirth of bature, of flocks, herds and shepherds. The feast day of the saint, April 23 /May 6 is the beginning of agricultural work, the hiring of farm hands for the season, St.George’s day is also the Day when haidouks took to the mountains. The Feast is celebrated a sacrificial lamb, at an open-air feast, and swinging of maidens in swings as a courting rite. The popular concept of St.George is connected witrh the hero, who killed the dragon, who had held back the waters and nature came back to life. The saint is the character of many a folksong where is he is presented as a farmer, making his round of the his fields and blessing the harvest.

St.George is among the most popular personages in fine art (Mazal 1990; Атанасов 2001; Walter 2003). Images of the saint to the East of the Balkans, as well as in church wall painting are based on the earlier Byzantine system of veneration of saints and followed the stylistic line of Orthodox Christian art. The development of iconography follows the evolution of the concepts here over the centuries. At first St.George is venerated as a Christian martyr and in icons he is holding a cross of the martyr; later he is seen as assisting in the battles as one who is triumphant – he is depicted with sword or spear and shield, wearing chainmail; subsequently St.George the warrior appears on a horse and afterwards becomes the most common image. According to this iconographic model St.George is depicted riding on a white horse, riding from the left to the right, with a red chlamys flowing in the wind. In his left hand he is holding the reins in his right hand, a long spear, piercing a monster, lying in the feet of the horse. Throughout the National Revival Period a boy with a water vessels in his hand appears, a reminiscence of one of the miracles of St. George, when St. George saves a youth from capture by the infidels.

Notes

Sources:

The Cult of St.George and the Zograph Monastery

Regina Kojčeva

Veneration of the martyr at Zograph was chiefly linked with the three miraculous icons of St. George, which are kept there to this day – the Phanouilian icon, the Saracen Icon and the Moldavian icon.

The news of the miracle quickly spread and a bishop came from Constantinople to examine how reliable the rumour was. Incredulous that the icon is not painted with paint, he touched it with a finger, and his finger stuck to it. The Bishop repented for doubting the miracle after which St.George appeared before him and told him that part of his finger would remain on the icon as an admonition to others.

The Saracen icon of St.George, dating from the 13th-14th century according to the legend came over the sea to Mt.Athos from Arabia and stopped on the coast opposite the Vatopedi monastery. As all monasteries at Mt.Athos wish to possess it, monks decoded to place th icon on th back of an untrained mule, which brought it to one of the hills facing Zograph. Later a church was built in honour of St.George on the spot.

The Moldavian icon of the Holy martyr was originally donated by the Byzantine Emperor John Palaelogus to the Moladvian voivod Alexander the Good (1400–1432). The icon reached Zograph as a gift from the Moldavian ruler Stefan the Great (1457–1504). According to the ruller’s statement, St.George appeared before him, to support him before a war with Turkey and the saint himself after the victory gave instructions that the icon be presented to Zograph. At that time Zograph was abandoned owing to numerous attacks and plundering. After the successful outcome of the war the Moldavian voivode carried out the instructions of the saint and together with the icon donated much money to monastery, which helped it to recover.

Besides the three miraculous icons of St.George the Vita of the Reverend Pimen of Zograph, who lived in the second 16th century and the early 17th century was directly connected with the cult of the martyr at Zograph. According to hagiographical information the marty appeared many times before the reverend Pimen and ordered him to leave Mt.Athos and preach in the area of Sofia, where he came from. Thus according to the will of St.George Pimen of Zograph, built about 300 churches and 15 monasteries around Sofia, decorating part of them himself. It was not by chance that the date of his death was November 3rd 1610, which coincides with the day of the Autumn feast day of St.George.

List of Manuscripts and XML encoding

For the preliminary variant of XSL transformation of XML to HTML please use recent version of Firefox (Seamonkey) or Opera. This variant still does not work with the Internet Explorer.

This version is still very alpha quality. It needs improvements in design. The links in this version do not function. We are in process of constructing a central repository for bibliography and reference works called Libri Slavici which will available in the second half of the 2008.

You could browse the content of the whole directory here.

| Signature | Manuscript Name | XML (View in Firefox) | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| I.д.2 | Apostolos of Laloe | ASO_MSS_ZM1d2.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.б.3 | Homilies and Sermons by St. Basil the Great | ASO_MSS_ZM1b3.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| RNL, Q.п.I.35 | Tetraevangelion | ASO_MSS_ZMQpI35.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.e.10 | Tetraevangelion | ASO_MSS_ZM1e10.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.a.1 | Tetraevangelion | ASO_MSS_ZM1a1.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| Austria, ÖNB 42 | Miscellany | ASO_MSS_ZM_ONB42.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.д.6 | Panegyrikon | ASO_MSS_ZM2d6.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.б.5 | Paterikon | ASO_MSS_ZM2b5.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.в.5 | Barlaam and Joasaph | ASO_MSS_ZM2v5.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.e.3 | Monastic Miscellany | ASO_MSS_ZM3e3.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| RNL, Glag. 1 | Codex Zogrphensis | ASO_MSS_ZM_Glag1.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.a.2 | Miscellany | ASO_MSS_ZM2a2.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.и.3 | Margarit by John Chrysostom | ASO_MSS_ZM1i3.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.a.9 | Sunday Sermons for the Lent | ASO_MSS_ZM3a9.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.д.2 | Menaion for June-August | ASO_MSS_ZM2d2.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.д.5 | Festal Menaion | ASO_MSS_ZM2d5.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| RNL, F.I.618 | Menaion for October | ASO_MSS_ZMFI618.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.a.7 | Miscellany | ASO_MSS_ZM3a7.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| Cat. Nr. 103 | Liturgical roll of Patriarch Euthymios | ASO_MSS_ZM103.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.г.12 | Leiturgicon of Patriarch Euthymios | ASO_MSS_ZM1g12.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.д.4 | The Ladder of Paradise | ASO_MSS_ZM3d4.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| Cat. Nr. 281 | Monastic Rules by St. Basil the Great | ASO_MSS_ZM281.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.д.9 | Hymnographic Works for St. George | ASO_MSS_ZM1d9.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.в.3 | Miscellany | ASO_MSS_ZM2v3.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.e.6 | Lental Triodion | ASO_MSS_ZM3e6.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.e.8 | Tetraevangelion | ASO_MSS_ZM3e8.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.д.4 | Miscellany | ASO_MSS_ZM2d4.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.д.8 | Miscellany | ASO_MSS_ZM2d8.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.з.8 | Zograph Bead-Role | ASO_MSS_ZM3z8.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.в.1 | Tetraevangelion | ASO_MSS_ZM1v1.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.б.8 | Tetraevangelion | ASO_MSS_ZM1b8.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.г.13 | Verse Prolog for the Whole Year | ASO_MSS_ZM1g13.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.д.2 | Apostle | ASO_MSS_ZM1d2.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| Cat. Nr. 171 | Psalter with Supllements | ASO_MSS_ZM171.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| II.б.1 | Psalter | ASO_MSS_ZM1b1.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.e.15 | History of Bulagaria (Istoria Slavjanobolgarskaja) by Paisij Hilendarskij | ASO_MSS_ZM1e15.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.a.1 | Leiturgikon | ASO_MSS_ZM3a1.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| III.з.10 | Vita and Service of Cosmas of Zohraphou | ASO_MSS_ZM3z10.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.e.12 | Tetraevangelion | ASO_MSS_ZM1e12.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| Odessa, 1/4 and 1/5 | Festal Menaion of Dobrijan | ASO_MSS_ZM1_4-1_5.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.e.9 | Festal Menaion of Dragan | ASO_MSS_ZM1e9.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.e.7 | Menaion for September-November | ASO_MSS_ZM1e7.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.д.13 | Psalter of Radomir | ASO_MSS_ZM1d13.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

| I.д.4 | Triodion of Gruban | ASO_MSS_ZM1d4.xml | Diljana Radoslavova |

Sources:

Bibliography

Bibliography of the Zograph manuscripts (Preliminary selection)

I. Codex Zographensis

II. Zograph Folia

III. Aprakos Apostle from the end of 12th or from the beginning of the 13 century

IV. Festal Menaion of Dobrian from the 13 century

V. Menaion of Dragan from 13 century

VI. Menaion for September, October and November from the first half of 13 century

VII. Psalter of Radomir from the 13 century

VIII. Lent Triodion of Gruban from the second part of the 13 century

IX. Apostle of Laloe from 1369

Х.Miscellany with homilies and of St. Basilius the Great

XI. Tetraevangelion from the beginning of the 14 century (1305 ?)

Tetraevangelion from the middle of the 16 century

XIV Zograph Miscellany (panegyrikon) from the last quarter of the 14 century

XV Paterikon from the middle of the 14 century

XVI Tetraevangelion from the first quarter of the 14 century

XVII „Barlaam and Ioasaphus“ from the third quarter of the 14 century

XVIII Monastic Miscellany from the end of the 14 century

XIX Miscellany of Vitas and Homilies from the third quarter of the 14 century

XX Margarit Miscellany by John Chrysostom from the third quarter of the 14 century

ХХI Menaion from the 1392

XXII Festal Menaion from the third quarter of the 14 century

-

II.д.5.